The Taberna della Venere, TDV, is very important in the research concerning the late antique phase of the shops overlooking the Forum square. The room apparently presents a situation very similar to that attested by the excavations of the Progetto Ostia Marina of the Università di Bologna (696 coins), with the same prevalence of coins from the end of the 4th – beginning of the 5th century CE, with a sequence that seems to start with the reign of Constantius II and be interrupted around the 440s (the terminus post quem coin is a nummus of Valentinianus III minted around 435 A.D.). In the case of the Ostia Marina Project, the sequences of clay and silt levels suggest that the burial of the site would have occurred following flooding of the Tiber and/or the sea.

As we do not have any other indications about the use of this structure, we can rely on some archaeological data that can lead us to suppose the activity that took place there. The analysis of the numismatic material is proving to be particularly important in answering this question.

The coins found during the excavation of these two rooms are 558 from TDV 1 and 18 from TDV 2. The great difference in the number of coins from the two rooms is quickly explained; in TDV 1 the excavations were carried out over the whole surface of the room, finding sealed and representative contexts, while TDV 2 was investigated only near the doorway that divides it from TDV 1, as there the archaeological context was damaged by more recent excavations. Of these big number of coins, most are illegible, either because they are very worn and/or have been fragmented already in antiquity, or because they are deeply corroded or affected by bronze cancer. The poor legibility of coin finds from this period is not surprising, as even 4th-5th century hoards are often in fair condition, for example in the Portus hoard only a quarter of the total coins (77 out of 200 specimens) were legible. Another reason why coins from the Late Antique period (especially those from the 4th century) are very often illegible is the prolonged circulation of these coins and their residuality in contexts long after they were issued. An example of this is certainly the analysis of coins from Portus, where 4th century specimens are documented in phases datable to the second half of the 6th century.

The access to the deposits was impossible due to the pandemic, so no cleaning of the surface soil of the coins was carried out during this year, which would have been indispensable for a secure data. Fortunately, most of the coins had already been weighed and measured at the time of discovery, and a selection of coins had already been surface cleaned, so their identification and cataloguing was possible.

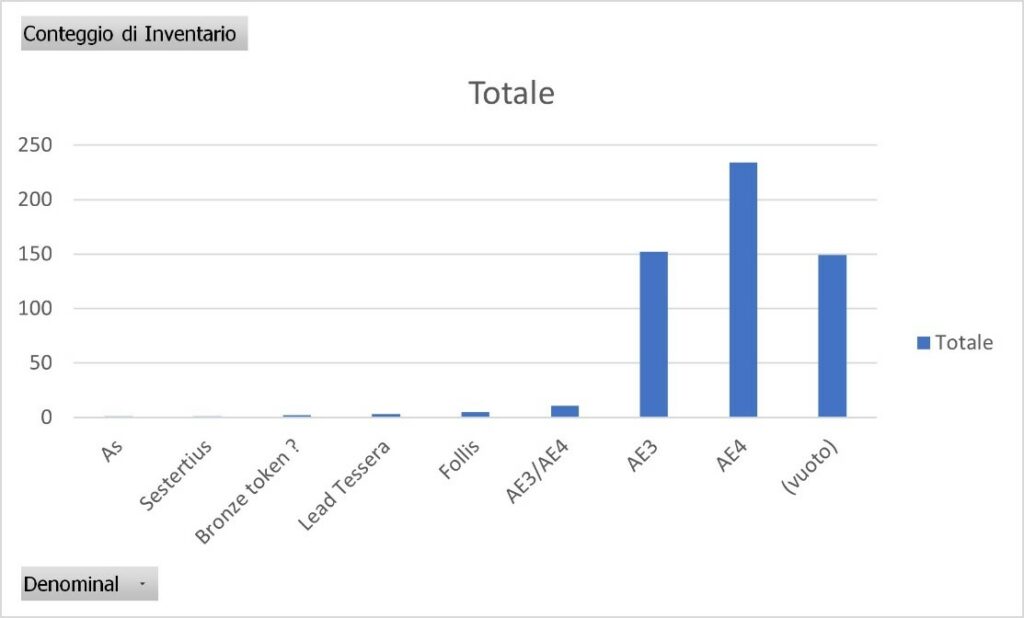

Of the total 558 coins, there are complete measurements of 409 specimens. Among these we have sporadic older denominals, such as the as and the sestertius, while 2 appear to be bronze tokens and 3 are lead tesserae. The majority of the coins are small denominals, such as the AE3 (in the number of 152 specimens) and the AE4 (234 coins). In addition, 11 coins that straddle the two denominals (AE4 under 14 mm. in diameter and 1.5 g. in weight) were counted separately, while taking into account the weight variation due to corrosion, wear and surface encrustation.

The coins for which we have a complete cataloguing are 97 specimens and it is this group that will be examined in detail below.

Among the mints identified so far, Rome is certainly the most present, with 15 coins, while others come from the workshops of Siscia (5), Aquileia (3), Cyzicus and Arelate (2 each). Among the datable coins, the later ones, from Galla Placidia to Valentinianus III, including Theodosius II (8 coins), we can see that all the recognisable mints of issue are Rome (6 specimens). What emerges is a general context of affirmation of the small circulating currency, which is generally considered to be conditioned by the production of the nearest local mint. Very interesting is the information that emerges from the coins found during the Classe excavations in Ravenna. In the period 378-395 CE, the specimens that can be traced back to the production of a specific part of the Empire are equally divided between Eastern and Western mints, while in the following period (395-455 CE), Western productions related to Honorius and Valentinianus III are abundant. Thereafter, an equal division between the mints of the two parts of the empire returns. This period corresponds to the important reorganisation of the Roman mint in the Theodosian age and under the last of the Valentinians. A complete break in style and fabric occurs about half way through Valentinianus III’s reign, suggesting a change (not for the better) in the personnel of the mint. After his death, the output of bronze declined sharply.

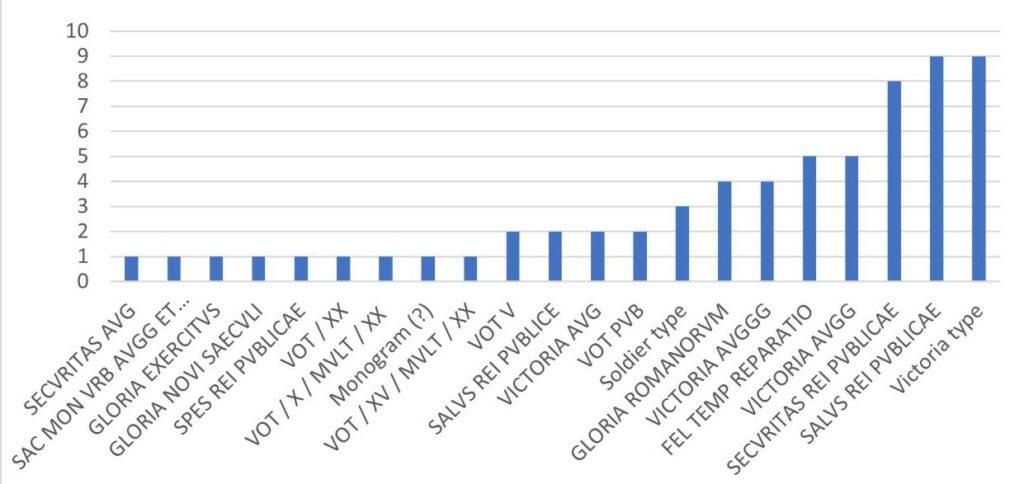

Most of the depictions on the reverse are typical of 4th-5th centuries coins, like the winged Victoria, with the legend SECVRITAS REI PVBLICAE or SALVS REI PVBLICAE/SALVS REI PVBLICE (28 coins). Other well represented reverses are those with the two Victoriae and the legend VICTORIA AVGG and VICTORIA AVGGG (9 coins). Of great importance is a Vota Vicennalia of Valentinianus III, which will be analysed specifically for the philological problems it presents.

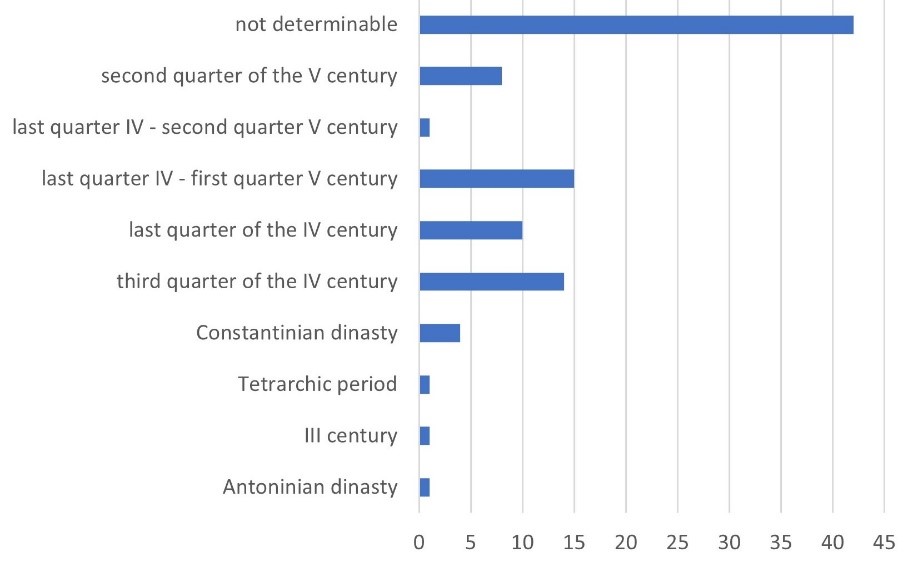

Because of their poor preservation, the coins for which it was possible to recognise the type on the reverse have been placed in a more or less broad chronological horizon.

The large number of undated coins (42 coins, 40,74 % of this selection) are mostly corroded and completely illegible flans, mostly AE4 (27 coins) and AE3 (11). Of the coins that can be dated, the 46.56 % (48 specimens) are coins dating from the mid-IV century to the 430’s. The oldest coin is an as minted during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (172-180 CE) with the representation of a Victoria on the reverse, unfortunately in fair conditions (context 002a). The coin shows heavy wear, probably due to prolonged circulation time or prolonged rubbing (it cannot be excluded that it was carried by water or debris). The presence of such an old coin is not surprising in relation to the dating of the strata formation from which it came, as bronze coinage, even of old issue, was used for much of late antiquity. From context 004 comes an ancient specimen in good condition, it is a sestertius of Gallienus with the legend SECVRITAS AVG, dated at the 253-260 CE.

Thus, with the exception of a few sporadic specimens, we can say that the coins in this selection were minted from the Constantinian era until the second quarter of the 5th century, with a high concentration of denominals from the second half of the 4th century. The coin data in TDV are consistent with those from the Late Antique strata of the Basilica Portuense, where there is a very high attestation of 4th century coins and an abrupt stop during the following century. In contrast to the Basilica, in the TDV we apparently have no attestation of 6th and 7th century coins. The numismatic data published so far, from the excavations of Castrum Novum (Santa Marinella, Rome), which are still in progress, seem to attest to an exploitation of the area until the middle of the 5th century, with the presence, also in this case, of 4 coins attributed to Valentinianus III, as well as a thickening of specimens at the turn of the two centuries. Among the coins found in the TDV, special mention should be made of the voluntarily cut coins, which number about 129 (the 23.04 % of the total coins). The division mainly concerns coins such as AE3, which were split into two or more parts, so that they are equivalent in weight to the AE4 of the late 4th-5th centuries, although AE4 are also present split down the middle.

Vota soluta or Vota suscepta?

The AE4 minted in the name of Valentinianus III and celebrating the Emperor’s Vota Vicennalia, found in context 004a, needs a specific historical-numismatic analysis to be dated accurately.

Fig. 1. 2:1 [VALE] NTINI [ANVS PF AVG], VOT / XX, 11-12 mm., 1,47 g., 434-435 AD.

Vota are promises made to gods’ conditional upon receiving specified benefits, sharply contrasted with free-will offerings. Despite this, there was a tendency for emperors, from Commodus at least, to hold a consulship in quinquennial years that this tendency became an almost invariable rule in the 4th century and was strongest in the 5th. Vows for the decennalia alone could look ahead both five and ten years, with VOT X MVLT XV and VOT X MVLT XX both being found; formulae such as VOT XX(X) MVLT XX(X)V never appear. Single figures are often difficult to evaluate: VOT XV and VOT XXV, for example, are always soluta, but VOT X or VOT XX can be either soluta or suscepta. Valentinianus III has only bronze issues marking his vicennalia. He was consul in 425, 426, 430, 435, 440, 445, 450, and 455, and his quinquennial years would have been 23 October 429 to 22 October 430, 434-5, 439-40, 444-5, 449-50, and 454-5. The VOT XX could, however, be suscepta and refer to the decennalia.

From the area where the Taberna counter was to be located comes what has been identified as a lead scale weight. The shape is that of a globe with a flat side, on which is soldered what must have been an iron hook, thanks to which the weight could slide on a steelyard. The weight is over 200 grams and is 9 cm. wide.

Unfortunately this type of weights have been used for centuries and do not have a precise chronological horizon. From the same layer comes a large shell, in particular is a Charonia Tritonis specimen shell, a gasteropod relatively widespread along the Eastern and Western Atlantic Coasts, from the Cape Verde Islands to the African Coast and from North Carolina to Brazil. In Italy, it is found in the waters of the central and southern Tyrrhenian Sea and in the southern Adriatic Sea. In the Mediterranean Sea, it is most common in the eastern part, particularly in Greek waters. It could therefore be a shell that arrived in the TDV as a result of the trade that might have taken place there.

As far as iron materials are concerned, a ring with a small stalk is of interest (TDV 1 001, 40 mm., 6,95 g.). It might be interpreted as part of a wall ring, with the stalk embedded inside the wall. Another possibility is that it was the end part of an iron key, or the end part of a knife.

From the surface layers, close to the lead weight (001, 001a) come two other noteworthy objects; a fragment of pie and what appears to be a guide for hinges, both made of lead.

The coins found in the sealed layers of the room are certainly a large number, but as they are exclusively bronze coins, their purchasing power is very low. In order to appreciate the value of these coins at the half of the 5th century, we have to mention the famous Novella XVI of Valentinianus III of the 445 CE, in which the collectarii were granted the price of 7000 nummi in exchange for one solidus. Thus, the coins found may have been used to buy and sell goods that were not particularly expensive, such as food. All these clues, are compatible with the use of the room as a Taberna, probably for the sale of shellfish, but also with a shop linked to the activity of a currency exchange.

As far as bronze finds are concerned, only two objects in this material were found in the TDV. One is what appears to be an ornithomorphic fibula or flat type with rectangular ring, highly corroded. The first type seems to find comparisons with fibulae found in Viminacium (Serbia) and the second with specimens found in Südtirol and Trentino, dating to the Late Antique period.

The second item is a cut, rectangular bronze sheet, with a hole and a sort of relief decoration. It is not easy to attribute a function to this object, as it could be part of a harness, just as it could be part of the decoration of a piece of furniture or a casket.

The reuse after the Taberna phase

The accumulation of marble fragments from the superficial layers of the southwest corner of the room, removed during the 2015 excavation campaign, indicate a reuse of the room after its destruction around the middle of the 5th century. A coin, attributable to the reign of Zeno (474-491 CE), found in the level of the marble accumulation, may suggest a superficial cleaning of the room from the rubble and an almost immediate reuse of the structure. Other objects worth mentioning are the lead slugs found in various areas and contexts of TDV, some of which are considerable in size and weight (well over 200g). Such a quantity of molten metal slag could make one think of the processing waste of a factory dedicated to the production of lime, using ancient marble, in this case lead could be the claws that could join parts of marble.

Conclusions and perspectives

The large amount of numismatic material presented here needs a thorough study, which will be resumed as soon as the health situation makes it possible. The proposed identification as a Taberna for the sale of seafood derives from the interpretation of the data just described, but also the hypothesis that it was a currency change office cannot be ruled out. That said, a full comparison with the other classes of material found will be needed in order to get a complete analysis. The numismatic data analysed so far is consistent with those from other excavations of this period. Above all, it should be noted that the abrupt interruption of circulating coins can be dated to around the 440’s, since the most recent group of coins are nummus of Valentinianus III. This seems to indicate that there was a particular event that marked the end of activities in the Taberna della Venere around that time.

You can find more here.