INTRODUCTION

Between the summer of 2021 and the winter of 2022, the cleaning of the entire core of coins from the Taberna Della Venere was continued and completed, with a total of 605 coins. Once cleaned, double-sided photographs were taken, post-production work was done for each of the 1210 photos and the relevant descriptive sheets were filled in. In addition, an Excel spreadsheet was produced to be used as an inventory for the numismatic finds.

At the present stage of the works, it is possible to obtain definitive data regarding the numismatic materials found in the Taberna Della Venere.

Among the 605 coins, 311 AE4, 225 AE3 (including the fractional coins that can certainly be identified in this denominal), 38 specimens that, either because of corrosion or because of an irregular roundel, show characteristics that make it difficult to attribute them to one or the other type, 14 follis (of which only two predate the reductions in weight in the bibliography, while 10 are “light” from the Constantinian dynasty), 3 antoniniani, 2 asses, 1 sestertius, 1 probable provincial bronze, 4 leaden tesserae and 6 coins that, due to their lying in damp soil, have lost any characteristic that makes them recognisable from the shape of the flan (but certainly not AE4 or AE3).

The chronological span covered by these numismatic finds goes from the Trajan era to the reign of Zeno (476-491 A.D.). Although these coins are sporadic, the fact that they both come from sealed contexts makes their discovery very interesting, in terms of hoarding in the first case and as terminus post quem in the second.

Due to the generally low conservation, only 34 coins could be attributed a reference bibliography. In total, 385 coins were illegible (including coins in which only the portrait features of the obverse could be recognised), i.e. 63.4% of the total. Some of the flans appear almost as if they had not been minted, as their surface appears smooth and without any apparent traces of relief, but this characteristic can only be attributed to a long circulation of the coin itself.

METODOLOGY OF CATALOGUING

The manuals used for cataloguing the coins from the Taberna Della Venere comprise almost the entire body of literature on late antique coins. Due to the poor preservation of the material, great use was made of the volume of Guido Bruck[1], in the recent version translated into English. For the distinction of the smaller denominals it was decided to refer to the standard in RIC X[2], and therefore to recognise the AE4 in coins weighing less than 1.50 grams and with a diameter of less than 14 mm, while the AE3 in specimens weighing between 1.50 and 4 grams and with a diameter between 14 and 18 mm. Because of the wide chronological span between the oldest and the newest coinage in the TDV, several volumes of Roman Imperial Coinage have been used, in particular those from V-1 to X[3]. The Late Roman Bronze Coinage[4] has also been used extensively, especially for the part concerning the dating of issues that had a longer course. For monogrammed coins a thematic publication was consulted[5].

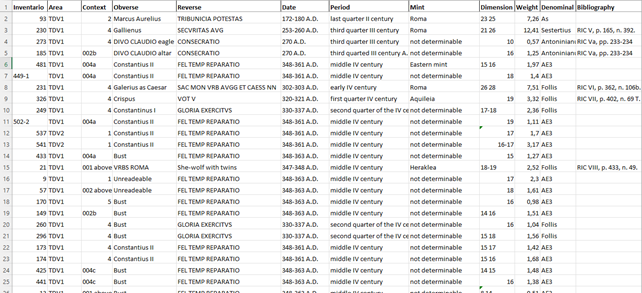

THE EXCEL SPREADSHEET

The complete Excel document has been sent to the direction of the Parco Archeologico so that it can be used for future research by academics. The columns relevant to the entire numismatic nucleus found inside the Taberna Della Venere have been set up and filled in, and the following data have been reported:

– Inventory number: for now this is an internal numbering of the excavation of Ostia Forum Projekt, the ideal prospect would be to replace this data with a definitive inventory number found in the archives of the Parco.

– Area: in our case it indicates the Taberna Della Venere, with a division into TDV1, if it is the main room thoroughly investigated, and TDV2, when it is a coin found in the surface layers cleaned inside the second room.

– Context: the layer or context of origin. In the case of layer 001, particular care was taken to highlight which of the two rooms the coin came from, as it is a layer shared by both.

– Obverse: the so-called “obverse” of the coin usually contained the portrait of the Emperor (or a family member or usurper) and the legend with his name and title. It was preferred to indicate the full name, even if it was only possible to read it in part, while in the many cases where it was not possible to read the name but only see the portrait, “Bust” was generically indicated. If not even the features could be read, this was indicated as “Unreadeable”.

– Reverse: the column shows the legends on the reverse side of the coins, even if these are not legible but it is still possible to attribute the coin with certainty to the relevant series of issue. For a much-discussed issue from the late 4th-5th century, such as the one with the figure of the Victoria incedent on the left, the precise legend has been indicated if it is identifiable, otherwise a generic ‘Victoria type’ has been preferred. As for the reverse, if it is not possible to identify anything on the surface of the coin, it has been indicated as ‘Unreadeable’.

– Date: the period in which the particular coin series was minted is indicated, sometimes to the year in special cases (such as for coins indicating the Vota or other precise anniversaries).

– Period: this is an additional indication to the “dates” column, very useful in the drafting of graphs that can include the totality of the material studied, without being too dense.

– Mint: indicates the city where the coin was minted. For some coins where the indication in the exergue was not legible, it was possible to indicate whether the coin was from an eastern mint, using stylistic comparisons for the portrait or epigraphic comparisons on the reverse.

– Dimension: indicates the diameter of the coin. Two numbers are commonly given, the maximum and minimum diameters, as the flan especially in the late antique period, tend to have irregular shapes.

– Weight: the column shows the weights of the individual coins, expressed in grams and with an indication up to tenths of a gram.

– Denominals: with this term in numismatics the type of coin is expressed, it is therefore indicated whether it is an as, a sestertius or other smaller modules, introduced after the reform of Constantius II of 348 AD, the AE3 or AE4.

– Bibliography: only for some coins, for which it was possible to read the legends and the exergue, it was possible to indicate the reference bibliography.

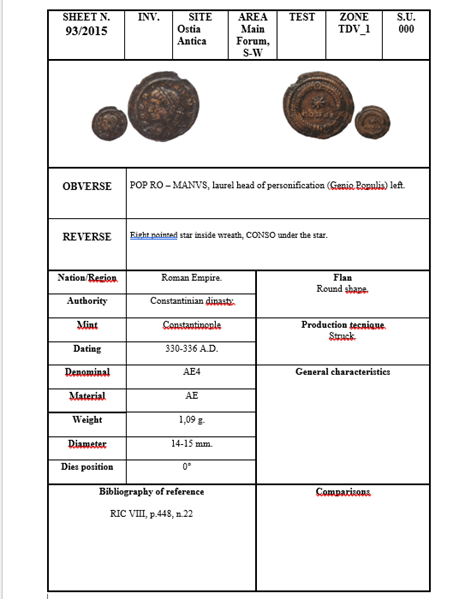

DESCRIPTIVE SHEETS

The data present in the Excel sheet are substantially reported, with the addition of the “Dies position”, that is the positioning (expressed in degrees) of the die of the reverse with respect to that of the reverse. This is particularly important for understanding the type of dies used. Especially in the late antique period, we have clear evidence of the so-called “pincer dies”, in which the coin was positioned to be minted. The fact that they were fixed can be seen from the coins, which usually have an orientation of the minting of the obverse with respect to that of the reverse of 0° or 180°.

The inscriptions present in the legends, in the exergue, in the coin fields has been read and transcribed using the following diacritical marks:

“ / ” = indicates the arrangement of the text on two different lines.

“ – “ = indicates a separation within a normally joined word.

[abc] = integration of reconstructible gaps.

{abc} = deletion of letters considered superfluous.

[. . .] = unreconstructible gap, of which the number of letters is known, each point indicates a missing one.

[- – -] = unreconstructible gap, of which the number of letters is unknown[6].

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Once the lengthy process of cleaning, cataloguing, photographing and arranging the data has been completed, it is planned to write an article in the near future as a preview of what will become the body of the PhD thesis. With the definitive data it will be possible to compose graphs that will allow an immediate and intuitive understanding of the numismatic material found in the various layers of the Taberna Della Venere. The work carried out will also be useful to the archives of the Parco Archeologico di Ostia Antica in order to have an overview of the numismatic material found during the excavations of the Ostia Forum Projekt and to make the material easily available to academics who may request to study it in the future.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Buonopane 2009: Manuale di epigrafia latina, Carocci, Roma, 2009.

Bruck 2014: Late roman bronze coinage, An attribution guide for poorly preserved coins, Geneva, 2014.

Bruun 1966: The Roman imperial coinage. Volume VII, Constantine and Licinius A.D. 313-337, London, Spink & Son, 1966.

Hill – Carson – Kent 1960: Late Roman bronze coinage, A.D. 324-498: part I: The bronze coinage of the House of Constantine, A.D. 324-346 / — part II: Bronze Roman imperial coinage of the later Empire, A.D. 346-498, London, Spink & Son, 1960.

Kent 1981: The Roman imperial coinage. Volume VIII, The family of Constantine I, London, Spink & Son, 1981.

Kent 1994: The Roman imperial coinage. Volume X, The divided Empire and the fall of the western parts AD 395-491, London, Spink & Son, 1994.

Morello 1999: Piccoli bronzi con monogramma (sec.V-VI), Libreria Classica Editrice Diana, Cassino, 1999.

Pearce 1951: The Roman imperial coinage. Vol. IX, Valentinian I- Theodosius I, London, Spink & Son, 1951.

Sutherland 1967: The Roman imperial coinage. Volume VI, Diocletian’s reform (A.D. 294) to the death of Maximinus (A.D. 313), London, Spink & Son, 1967.

Webb 1927: The Roman imperial coinage. Vol. V, part I, London, Spink & Son, 1927.

Webb 1933: The Roman imperial coinage. Vol. V, part II, London, Spink & Son, 1933.

[1] Bruck 2014.

[2] Kent 1994, p. 17.

[3] Webb 1927; Webb 1933; Sutherland 1967; Bruun 1966; Kent 1981; Pearce 1951; Kent 1994.

[4] Hill – Carson – Kent 1960.

[5] Morello 1999.

[6] Buonopane 2009, pp. 136 s.