Outline of the Thesis – Deposits and Sacrifice in the Sanctuary of TFR2

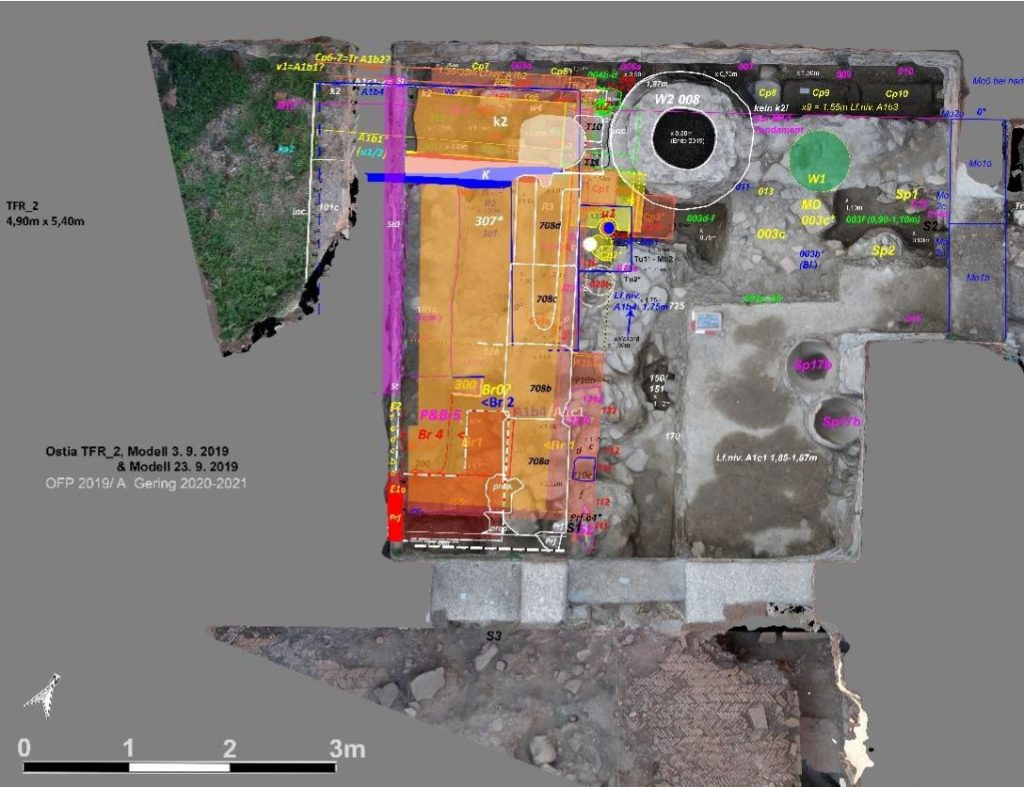

This thesis examines the religious deposits and cult practices from the newly discovered sanctuary on the Forum of Ostia. The material derives from the excavations conducted by the OFP between 2016 – 2019. In the room called TFR2 (Taberna Forum Room 2), the remains of a previously unknown sanctuary were discovered. The remains included an altar (A1b/c), drains, a well, and several religious deposits, which mostly contained ceramic material. This thesis wishes to examine these religious deposits and other material from the sanctuary to understand the religious practices conducted in the sanctuary. The following report includes some of the current theories about the material.

Method and Theory of Pottery Agency

The religious deposits were found spread out in most of the TFR2, however, a majority of them were found in the area around the structures, especially the drains and the altar. The date of the deposits ranges from the republican period to the imperial period. The earliest material dates around the middle of the third century BCE and the latest to the end of the second century CE. To study the deposits, I have chosen to focus on three defining elements: placement, structure, and contents. The placement: in what area of the sanctuary was the deposit placed. The structure: the structural definition of the deposits. As in closed off or walled off, but also the way the vessels were placed in the deposit. And lastly, the contents. In archaeological research, religious deposits have not been ignored as a subject, but have often been studied in a way that ignores the context. This is because the classification of individual objects is essential to archaeological research, especially when creating a relative chronology, which has always been a vital part of understanding a site. However, ignoring the identification and classification of religious deposits as a collected context limits the information we can collect from the sanctuary.1 In this thesis, I want to treat the deposits both as a context, while also making a classification of the individual objects. A classification of the deposits themselves, their placement on the site, the way they are structurally defined (or not) as well as the contents, will give an interesting insight into the repetitiveness and the development of cult practices in the area. A comparative analysis would also be interesting to see these systems of deposition consistency within the region of Lazio. Rituals are the physical manifestation of religious practice. They are, from an archeological point of view, difficult to reconstruct. The physical actions of ancient people are an elusive subject to study since objects are not actions but simply a result thereof. Rituals do not necessarily adhere to logic because they are “special actions which are somehow connected to a belief system”.2 The objects that most frequently end up as evidence of ritual are those belonging to “votive religion”. However, the term “votive” is very broad and often misused. The issue is that votive religion is vast, with many different types of objects. In TFR2 the majority of the “votives” are pottery. Pottery is one of the most frequently found objects in religious contexts. Ceramic vessels found in sanctuaries were not always developed with a religious purpose in mind but are also commonly found in domestic contexts. Vessels such as a patara has an obvious agency within a religious context, however, it can be argued that common cooking vessels found in sanctuaries hold the same level of agency. Ceramic vessels usually have two purposes within a sanctuary. They were used to contain offerings or cook cultic meals. As such pottery was highly connected to the most important aspects of cultic activity.3

Religious Structures in TFR2

The room TFR2 only encompasses a small part of the sanctuary, however, contains some important structures, which can reveal elements of the cult practices conducted in the area. The main structures of this area are the altar (A1b/c), a libation hole, a well, and the drains that run behind the altar.

The Altar4

During the campaign of 2021, a lot of new information on the altar was discovered. This was mostly from reexamining the many tuff blocks that had been found inside TFR2. Many of these blocks did seem to belong to different phases of the altar. A reexamination of the Hadrianic walls also revealed that part of the profile of the altar was preserved in the wall. The altar takes up most of the western side of TFR2, with around 1/3 of the altar covered by the wall. A1b/c is made of tuff and had several phases, all built on top of each other. The practices of building altars in the same location are very common. However, it makes it difficult to create accurate reconstructions of the altars, since newer phases cover and obscure the previous structures.

The altar in all phases consists of a tuff podium with a rectangular burning pit at the southern end. From the burning pit is a sloped ramp that leads to an opening to a sewer system linked to the Cardo-sewer. The altar has five phases. Phase 1 (altar A1b1) is defined by the lowest levels of the sewer. It has not been possible to identify a tuff podium for this phase, however, the presence of a sewer system is a strong indication that another altar podium is probably under the following altars. The first phase of the altar is difficult to date since only small parts of TFR2 have been excavated deep enough to get comprehensive material. What little pottery was found in this phase, suggests a date around the 2nd half of the 4th c – 1st half of the 3rd c BCE. Phase 2 has the first tuff podium and a rectangular burning pit. The sewer is continued in this phase at a higher level. The third phase (A1b3) is the first phase which has a podium with a decorated carved profile. From the third phase onwards, the altar seems to remain very similar in shape. The next big change is the fifth phase (A1c1). The altar contains its general shape but the main feature are now made of high-quality tuff blocks, this includes the podium, ramp, and drains. This monumentalized layout stayed in use until the early Hadrianic period and is the most well-preserved phase.

A1b/c was a U-shape altar, however, differs from many other U-shaped altars because the fire zone is on ground level or in a lowered area inside the structure of the altar. A1b/c has a burning zone, which is kept mostly in the same location but is raised as the altar and sanctuary change. In all phases of the altar, the burning zone was kept close to the ground level, with a slope leading from the burning zone towards the north and a drain, which also is present in all the altars phases. A1b/c continues its general shape until it is dismantled in the first century CE.

The continuity of the altar and its placement indicates a very strong tradition of religious practice connected to the structure. The shape and main elements of the altar not changing, could be an indication that the rituals connected to the sacred structure did not change for the 400 years it was in use. Interestingly, this altar was not changed but kept a very “old fashion” shape, while other sanctuaries in Ostia did not seem to have had an issue with changing the style of their altars. The closest comparison to the altar is the fire altar of Veii.5

Libation Hole

Another religious structure, connected to the altar on the eastern side, is several phases of a hole probably used for libations. The hole could have been used for libations of wine, oil, and possibly also blood, which would relate to the animal sacrifice conducted in the sanctuary.

The ‘libation hole’ exists from the second phase and was continued throughout the altar’s lifetime. In some of its phases (phase 2-4) the libation hole was marked or monumentalized in some way. However, no evidence suggests that this was the case in the latter part of the sanctuary’s lifetime.

The entrance of the libation hole was kept almost in the same position, probably only changing to follow the altar. The libation hole created a cavern in the dirt under it, which was one of the first elements of the sanctuary, which the OFP team found in 2016.

Animal Sacrifice and Faunal Remains

During the excavations of TFR2 between 2016-2019, a large number of faunal remains were found in the area. Because of the pandemic, this material group has not previously been examined and still needs to be examined by an expert. Animal bones and seashells were found in large numbers both in the deposits but also in the layers of the sanctuary. This is quite a contrast to the rest of the forum, which does not have as many bones in the layers. Burring the bones of sacrificed animals within a sacred area is very typical within Roman sanctuaries.

During the 2021 campaign, one of the focus points was to register the remains, especially the bones. There are several reasons that the animal remains could be interesting to examine further. A more in-depth study could identify which animals were sacrificed in the sanctuary, what age they had, if possible what gender they had, and if these factors change within the lifetime of the sanctuary.

The quantification of the bones has been a difficult task since there are no zooarcheologists connected to the project at the moment. It was, therefore, necessary to make thorough documentation of the bones, so a specialist could examine them at a later time. It has not been possible to specify the age of any of the animals, however, the purpose for making such a distinction will be discussed later. The following remarks have been made based on my knowledge and with the help of several guides to recognize different animal bones. The findings expressed here should therefore be considered preliminary.6

Many of the bones were splintered, broken, and burned, showing clear signs of cutting or chopping connected to sacrifice and butchering.7 This is to be expected, since animals were not just killed for the sacrifice, but were prepared and eaten in connection with ritualistic festivities. The bones, therefore, show signs of heating/cooking, and many have been splintered in the butchering and consumption of the animals. Because of this, it has not been possible to identify the species of every bone fragment found. In total 1438 faunal remains were found in TFR2. These account for both complete and fragmented bones. On average only 22% of the remains’ species could be identified and were thus included in the statistics. The majority of the faunal remains from this sanctuary stem from domestic animals: pigs, sheep/goats, and ox. In all phases of the sanctuary, the most common animal was the pig, constituting an average of 63% of the identified bones. Sheep/goat and cattle are somewhat evenly represented, at least in the phases that they both occur. In total, cattle only constitute 12% of the identified bones, while sheep/goats constitute 25%. Cattle are, however, not represented in the earliest phases of the sanctuary. This could indicate a change in the types of animals that were sacrificed in the sanctuary or an issue of a small material group. Further excavation of the lower layers of the sanctuary is required to make proper conclusions on this theory.

The average age of the animals has yet to be determined. However, through this preliminary examination, it is clear that not only one age group is represented. This is especially apparent with the pigs as it is themost plentiful species in the sanctuary. Remains of both piglets and adult pigs have been attested in various contexts. However, most bones seem to stem from adult or adolescent animals. The only animals whose age and sex have been determined are two of the pig skulls (S1-2) which were adult females of two years of age.

Faunal Remains from Deposits

A total of three pig skulls were found in the TFR-area: two of them in TFR2 (S1 and S2), as mentioned above, and one of them in TFR1 (S3). Both skulls found in the area TFR2 belonged to adult female pigs about two years of age. The skulls S1 and S3 were buried close to the altar, while S2 was found in the north-eastern corner of the area TFR2, near the bone deposits SU 014 and 016.

The skull S1 was buried at the south-eastern corner of the altar, probably either in phase 5a or 6.8 The pit in which it was deposited was dug in from a level of 1,96 m ASL and cuts through the SU 003a and 003b and into a previous pottery deposit (SU 112) from phase 5. The skull was surrounded by muddy clay and was bordered by two upright standing pottery fragments, which were placed as a boundary marker for the deposit.

The skull S2 was found in the north-eastern corner of the area TFR2, at the same level as the skull S1, dating it to the early Hadrianic phase 6, as well. The deposit of the skull was not dug through the mortar layer (SU 001c), which defines the transitional period of the sanctuary. Thus, the skull was deposited before the transition of the area from a sacred to a profane area started.

As mentioned above, the deposits SU 016 and 014 were placed in the north-eastern corner of the sanctuary. Both deposits were found immediately underneath the lowest layer of the marble deposit, which covered all of TFR2. The deposits were dug through the previously mentioned mortar layer (SU 001c) and must therefore have been made in the transitional period of the sanctuary (phase 6), possibly one of the very last sacrifices before the sacred area was closed. The deposits were closed-off in a very particular way: SU 016 was dug in right next to the later Hadrianic wall and bordered on its western side by several bricks, which had been stuck into the ground at equal distance. After the animal bones were placed into the pit, cooking ware lids were used to cover it. Some of the lids were found complete and placed leaning.

The bones recovered from the deposits 014 and 016 were better preserved than those found in other contexts. Most of them belonged to larger animals, i.e. an atlas and a shoulder blade from an ox. The shoulder blade had a length of 40 cm. Several near-complete jaws of pigs were also found in these deposits.

The depositions of the three pig skulls, 014 and 016 are the only currently known bone deposits in the sanctuary. Bones were a frequent find, both in deposits that mostly contained pottery and in the layers as well. At the moment, the skulls are being interpreted as a closing ritual of the sanctuary. The use of pig skulls as a closing ritual can be seen in Piano di Comunità in Veii9, where a well was ritually closed off by placing eight pig skulls inside before it was sealed. However, another example of pig skulls being buried in such a way is from the Palatine, at the sanctuary of Magna Mater. Here the skulls were interpreted as being part of the inauguration of the building, as they were found at the foundation of the porticus of Cybele.10

Inscribed Pottery from TFR2

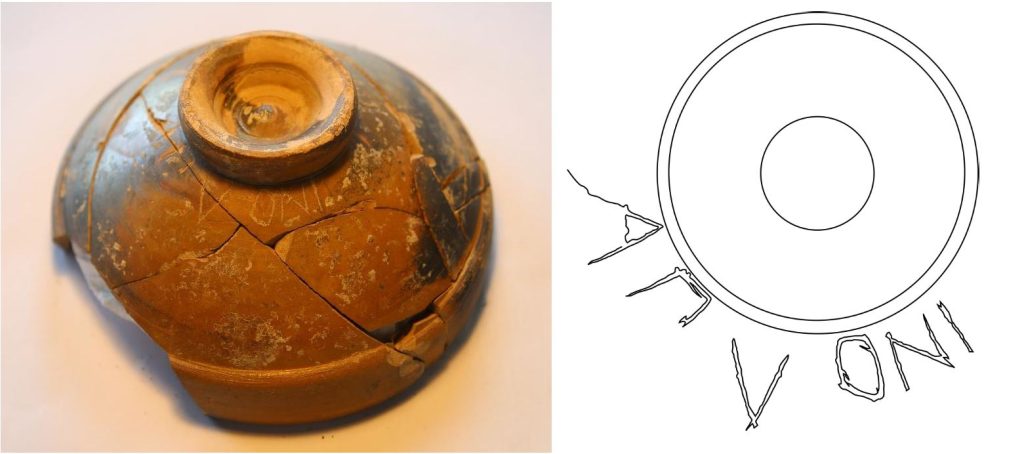

The opportunity to study the ceramic material, which had not previously been available brought on a lot of new exciting finds. Among these finds were several inscriptions in fragments of pottery as well as a complete inscription of a deity’s name.

In total five inscriptions have been found at this point. The four of them are made in black gloss vessels, while one is made in a cooking vessel lid. All the inscriptions have been made with a sharp tool after firing.

The first inscription is an A or X on the interior of the foot of a black gloss bowl. Such inscriptions have been found in other sanctuaries, however, the meaning of it is unclear. It could be a reference to the person who dedicated the vessel but is probably not a reference to the deity. Several A’s have also been found on pottery from other sanctuaries, such as Ardea11 and single letter inscriptions are in general common.12

Next is an A L (or an AU / AT but it is less likely) found on a cooking ware lid. The A is open with the line from the left and down. The type of A is common in the mid. republican period; however, the more common form of the letter has the line starting from the right.13 The inscription is most likely the name of the worshipper.

A fragment of a black gloss bowl has the inscription M I I on the lip. The inscription is possibly incomplete since the vessel is broken right before the M, which could mean that this is the end of the inscription. The M has a shape that dates to the 3rd century BCE.14 The I I should probably be read as an E, this type of E made with two vertical lines starts at the end of the 4th century but also appear consistently in the 3rd century BCE.15

Since the fragment was broken off right before the M but has no further letters after the I I, it is difficult to determine if the ME is the end of the name or is simply just an ME. ME could be the end of a female Greek-inspired name in the dative form. Another possibility is that ME could be a shortening io Menerva (Minerva), however, the inscriber has plenty of room to write the name out, so why shorten it.

A body fragment of a black gloss vessel had the letters I O (or I D) inscribed vertically on the exterior of the vessel. The letters had been made after firing, but unlike the other inscriptions which seem to have been carved with a pointed tool, this inscription was made by making make small “pokes” into the glaze. The fragment is broken right after the O, and it is, therefore, possible that the inscription is unfinished. Reconstructing the angle of the vessel and comparing it to similar bowls show that there would be room for another letter after the O. It is very possible that the fragment was supposed to spell IOVE, IOV, or IOVI, which would be a dedication to Jupiter.

The last inscriptions came from a black gloss bowl found in one of the deposits. The bowl is dated to the first half of the second century BCE (Morel 2534), however, the deposit is dated to the middle to late 1st century BCE. The vessel was placed inside the deposit with a thin-walled cup inside it. The bowl has an inscription on the exterior body, close to the foot of the vessel. The inscription was made with a pointed object post firing. It reads A P L O N I. The name is a Latin version of the Greek Apollon. This version of the name is most probably the dative version of the name, indicating that the offering was dedicated to Apollon.

The area under and around the A is broken, and it is, therefore, difficult to identify the exact shape of the letter. The next two letters are an open P and an L, which both point to a date in the late 4th century.16 The letters ONI, however, date to the 3rd century BCE. This leaves us with a date for the inscription probably at the beginning of the 3rd century.

References

1. Osborne 2004, 2-3.

2. Warden 2009, 107-110.

3. Rieger 2016, 309-310.

4. An article about the altar in more detail is upcoming by Gering, Menge, and Pedersen.

5. For more on the altar of Veii see Colonna 2011.

6. The following numbers and statistics are also part of an upcoming article by Gering, Menge, and Pedersen.

7. Noe-Nygaard.

8. For a better understanding of the levels and phases of the sanctuary, please see miss Menge’s work as my interpretation of the levels is based on that.

9. Ambrosini – Marchesini 2009, 264.

10. Coletti, Celant and Pensabene 2006, 560.

11. See Mento and Ceccarelli 2005.

12. Several examples can be seen again in Ardea, but also in Norba.

13. Ferrante and Nonnis 2018, 216.

14. Ferrante and Nonnis 2018, 216.

15. Ferrante and Nonnis 2018, 216.

16. Ferrante and Nonnis 2018, 216-217.

Literature

- Ambrosini L. and B. B. Marchesini 2009. “Ceramiche a Veio tra V e III sec. a.C.: I dati dello scavo di Piano di Comunità.” in Suburbium II: Il suburbio di Roma dalla fine dell’età monarchica alla nascita del sistema delle ville, V–II secolo a.C. V., edited by V. Jolivet, 1-27. Roma.

- Coletti F., A. Celant and P. Pensabene 2006. “Ricerche Archeologiche e Paleoambientali sul Palatino tra l’età arcaica e la tardoantichità – Primi risultati.” in Atti del convegno di Caserta, edited by C. D’Amico, 557-564. Bologna.

- Colonna 2002. Il santuario di Portonaccio a Veio. Rome.

- Ferrante S. and D. Nonnis. 2018. Ceramica Iscritta dai Dintorni Dell’Acropoli Minore di Norba. in Norba – Scavi E Ricerche, edited by S. Q. Gigli, 205-226. Rome.

- Di Mento M. and Ceccarelli L. 2005. La ceramica a vernice nera. Forme aperte. in: Di Mario 2005, 201–242.

- Noe-Nygaard, N. 1989. “Man-made trace fossils in bones.” Human Evolution 4(6): 461-491.

- Warden, P. G. 2009. “Remains of the Ritual at the Sanctuary of Poggio Colla.” in Votives, places, and rituals in Etruscan religion: studies in honor of Jean MacIntosh, edited by M. Gleba and H. Becker, 107-121. Leiden.