Search Results for: roma

Presentation in Rome

The Ostia Forum Project will be presenting in the international colloquium Urbs in transitum: innovazione e tradizione tra Roma e Ostia nel III secolo organised by Istituto Storico Austriaco, Academia Belgica and Parco archeologico di Ostia Antica. The colloquium will be taking place between October 4 and October 7 2023 in both Rome and Ostia.

The project is represented by the director, Prof. Dr. Axel Gering, and ph.d. student Sophie Menge. Their presentation is titled From sanctuary to shops. The transformation of the TFR-area northeast of the Forum from the 2nnd to the 3rd century AD.

2021-2022 Chapter 4. A Newly Discovered Sanctuary Under the Forum of Ostia – Sacrifice, Feasts, and Ritual Deposits

Outline of the Thesis – Deposits and Sacrifice in the Sanctuary of TFR2

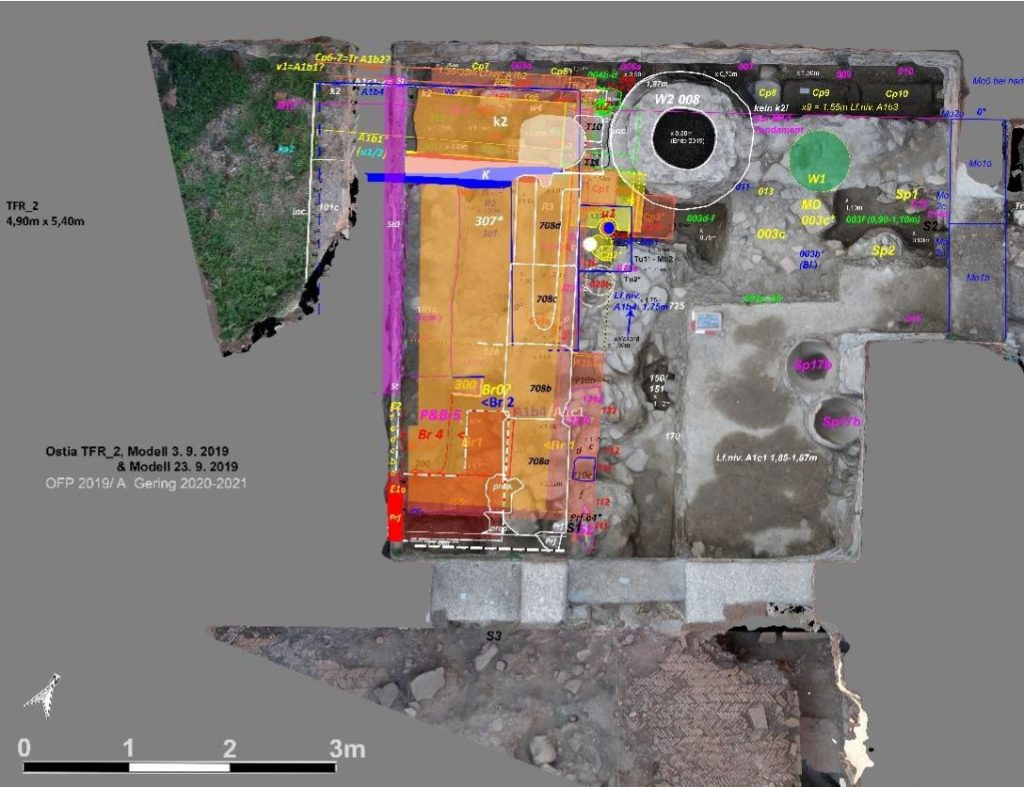

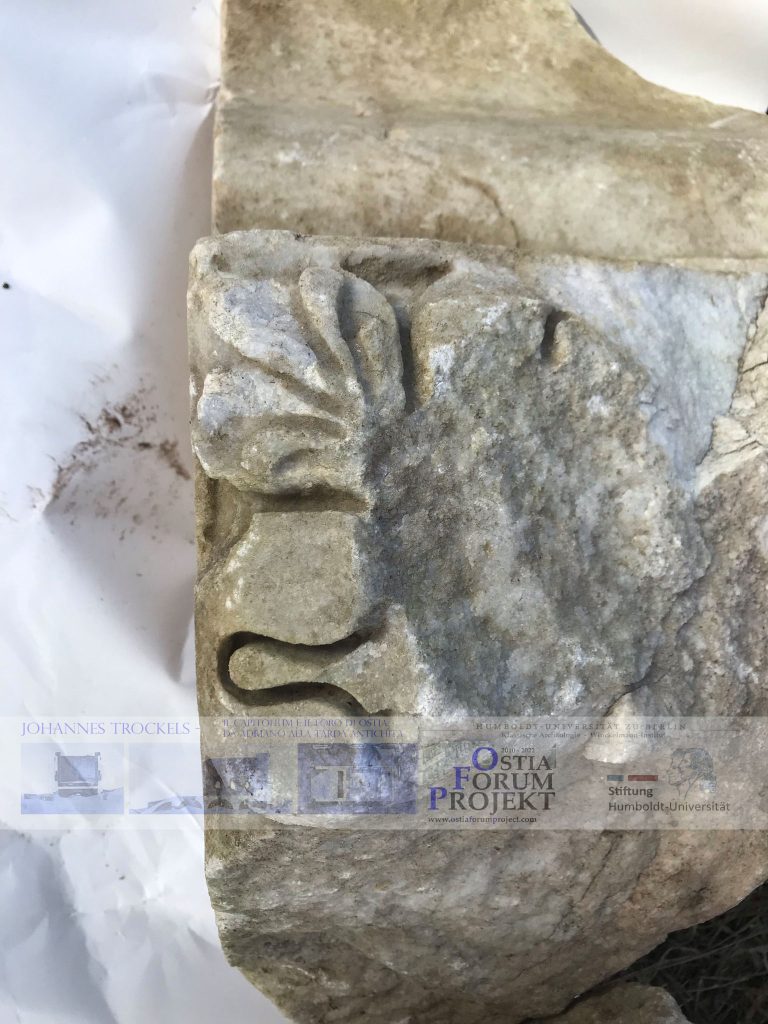

This thesis examines the religious deposits and cult practices from the newly discovered sanctuary on the Forum of Ostia. The material derives from the excavations conducted by the OFP between 2016 – 2019. In the room called TFR2 (Taberna Forum Room 2), the remains of a previously unknown sanctuary were discovered. The remains included an altar (A1b/c), drains, a well, and several religious deposits, which mostly contained ceramic material. This thesis wishes to examine these religious deposits and other material from the sanctuary to understand the religious practices conducted in the sanctuary. The following report includes some of the current theories about the material.

Method and Theory of Pottery Agency

The religious deposits were found spread out in most of the TFR2, however, a majority of them were found in the area around the structures, especially the drains and the altar. The date of the deposits ranges from the republican period to the imperial period. The earliest material dates around the middle of the third century BCE and the latest to the end of the second century CE. To study the deposits, I have chosen to focus on three defining elements: placement, structure, and contents. The placement: in what area of the sanctuary was the deposit placed. The structure: the structural definition of the deposits. As in closed off or walled off, but also the way the vessels were placed in the deposit. And lastly, the contents. In archaeological research, religious deposits have not been ignored as a subject, but have often been studied in a way that ignores the context. This is because the classification of individual objects is essential to archaeological research, especially when creating a relative chronology, which has always been a vital part of understanding a site. However, ignoring the identification and classification of religious deposits as a collected context limits the information we can collect from the sanctuary.1 In this thesis, I want to treat the deposits both as a context, while also making a classification of the individual objects. A classification of the deposits themselves, their placement on the site, the way they are structurally defined (or not) as well as the contents, will give an interesting insight into the repetitiveness and the development of cult practices in the area. A comparative analysis would also be interesting to see these systems of deposition consistency within the region of Lazio. Rituals are the physical manifestation of religious practice. They are, from an archeological point of view, difficult to reconstruct. The physical actions of ancient people are an elusive subject to study since objects are not actions but simply a result thereof. Rituals do not necessarily adhere to logic because they are “special actions which are somehow connected to a belief system”.2 The objects that most frequently end up as evidence of ritual are those belonging to “votive religion”. However, the term “votive” is very broad and often misused. The issue is that votive religion is vast, with many different types of objects. In TFR2 the majority of the “votives” are pottery. Pottery is one of the most frequently found objects in religious contexts. Ceramic vessels found in sanctuaries were not always developed with a religious purpose in mind but are also commonly found in domestic contexts. Vessels such as a patara has an obvious agency within a religious context, however, it can be argued that common cooking vessels found in sanctuaries hold the same level of agency. Ceramic vessels usually have two purposes within a sanctuary. They were used to contain offerings or cook cultic meals. As such pottery was highly connected to the most important aspects of cultic activity.3

Religious Structures in TFR2

The room TFR2 only encompasses a small part of the sanctuary, however, contains some important structures, which can reveal elements of the cult practices conducted in the area. The main structures of this area are the altar (A1b/c), a libation hole, a well, and the drains that run behind the altar.

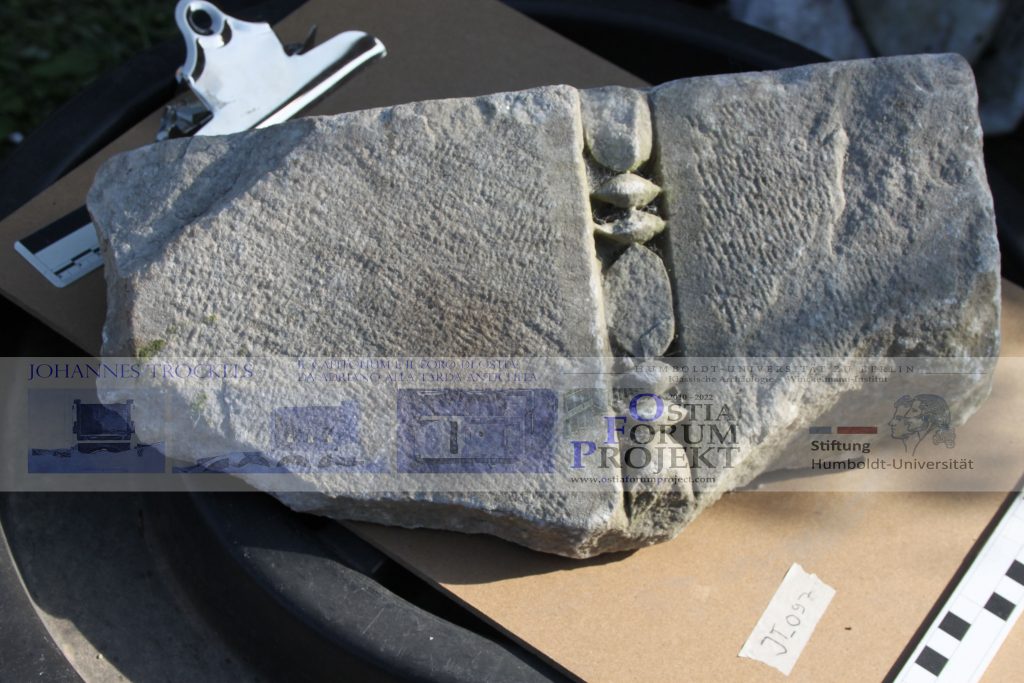

The Altar4

During the campaign of 2021, a lot of new information on the altar was discovered. This was mostly from reexamining the many tuff blocks that had been found inside TFR2. Many of these blocks did seem to belong to different phases of the altar. A reexamination of the Hadrianic walls also revealed that part of the profile of the altar was preserved in the wall. The altar takes up most of the western side of TFR2, with around 1/3 of the altar covered by the wall. A1b/c is made of tuff and had several phases, all built on top of each other. The practices of building altars in the same location are very common. However, it makes it difficult to create accurate reconstructions of the altars, since newer phases cover and obscure the previous structures.

The altar in all phases consists of a tuff podium with a rectangular burning pit at the southern end. From the burning pit is a sloped ramp that leads to an opening to a sewer system linked to the Cardo-sewer. The altar has five phases. Phase 1 (altar A1b1) is defined by the lowest levels of the sewer. It has not been possible to identify a tuff podium for this phase, however, the presence of a sewer system is a strong indication that another altar podium is probably under the following altars. The first phase of the altar is difficult to date since only small parts of TFR2 have been excavated deep enough to get comprehensive material. What little pottery was found in this phase, suggests a date around the 2nd half of the 4th c – 1st half of the 3rd c BCE. Phase 2 has the first tuff podium and a rectangular burning pit. The sewer is continued in this phase at a higher level. The third phase (A1b3) is the first phase which has a podium with a decorated carved profile. From the third phase onwards, the altar seems to remain very similar in shape. The next big change is the fifth phase (A1c1). The altar contains its general shape but the main feature are now made of high-quality tuff blocks, this includes the podium, ramp, and drains. This monumentalized layout stayed in use until the early Hadrianic period and is the most well-preserved phase.

A1b/c was a U-shape altar, however, differs from many other U-shaped altars because the fire zone is on ground level or in a lowered area inside the structure of the altar. A1b/c has a burning zone, which is kept mostly in the same location but is raised as the altar and sanctuary change. In all phases of the altar, the burning zone was kept close to the ground level, with a slope leading from the burning zone towards the north and a drain, which also is present in all the altars phases. A1b/c continues its general shape until it is dismantled in the first century CE.

The continuity of the altar and its placement indicates a very strong tradition of religious practice connected to the structure. The shape and main elements of the altar not changing, could be an indication that the rituals connected to the sacred structure did not change for the 400 years it was in use. Interestingly, this altar was not changed but kept a very “old fashion” shape, while other sanctuaries in Ostia did not seem to have had an issue with changing the style of their altars. The closest comparison to the altar is the fire altar of Veii.5

Libation Hole

Another religious structure, connected to the altar on the eastern side, is several phases of a hole probably used for libations. The hole could have been used for libations of wine, oil, and possibly also blood, which would relate to the animal sacrifice conducted in the sanctuary.

The ‘libation hole’ exists from the second phase and was continued throughout the altar’s lifetime. In some of its phases (phase 2-4) the libation hole was marked or monumentalized in some way. However, no evidence suggests that this was the case in the latter part of the sanctuary’s lifetime.

The entrance of the libation hole was kept almost in the same position, probably only changing to follow the altar. The libation hole created a cavern in the dirt under it, which was one of the first elements of the sanctuary, which the OFP team found in 2016.

Animal Sacrifice and Faunal Remains

During the excavations of TFR2 between 2016-2019, a large number of faunal remains were found in the area. Because of the pandemic, this material group has not previously been examined and still needs to be examined by an expert. Animal bones and seashells were found in large numbers both in the deposits but also in the layers of the sanctuary. This is quite a contrast to the rest of the forum, which does not have as many bones in the layers. Burring the bones of sacrificed animals within a sacred area is very typical within Roman sanctuaries.

During the 2021 campaign, one of the focus points was to register the remains, especially the bones. There are several reasons that the animal remains could be interesting to examine further. A more in-depth study could identify which animals were sacrificed in the sanctuary, what age they had, if possible what gender they had, and if these factors change within the lifetime of the sanctuary.

The quantification of the bones has been a difficult task since there are no zooarcheologists connected to the project at the moment. It was, therefore, necessary to make thorough documentation of the bones, so a specialist could examine them at a later time. It has not been possible to specify the age of any of the animals, however, the purpose for making such a distinction will be discussed later. The following remarks have been made based on my knowledge and with the help of several guides to recognize different animal bones. The findings expressed here should therefore be considered preliminary.6

Many of the bones were splintered, broken, and burned, showing clear signs of cutting or chopping connected to sacrifice and butchering.7 This is to be expected, since animals were not just killed for the sacrifice, but were prepared and eaten in connection with ritualistic festivities. The bones, therefore, show signs of heating/cooking, and many have been splintered in the butchering and consumption of the animals. Because of this, it has not been possible to identify the species of every bone fragment found. In total 1438 faunal remains were found in TFR2. These account for both complete and fragmented bones. On average only 22% of the remains’ species could be identified and were thus included in the statistics. The majority of the faunal remains from this sanctuary stem from domestic animals: pigs, sheep/goats, and ox. In all phases of the sanctuary, the most common animal was the pig, constituting an average of 63% of the identified bones. Sheep/goat and cattle are somewhat evenly represented, at least in the phases that they both occur. In total, cattle only constitute 12% of the identified bones, while sheep/goats constitute 25%. Cattle are, however, not represented in the earliest phases of the sanctuary. This could indicate a change in the types of animals that were sacrificed in the sanctuary or an issue of a small material group. Further excavation of the lower layers of the sanctuary is required to make proper conclusions on this theory.

The average age of the animals has yet to be determined. However, through this preliminary examination, it is clear that not only one age group is represented. This is especially apparent with the pigs as it is themost plentiful species in the sanctuary. Remains of both piglets and adult pigs have been attested in various contexts. However, most bones seem to stem from adult or adolescent animals. The only animals whose age and sex have been determined are two of the pig skulls (S1-2) which were adult females of two years of age.

Faunal Remains from Deposits

A total of three pig skulls were found in the TFR-area: two of them in TFR2 (S1 and S2), as mentioned above, and one of them in TFR1 (S3). Both skulls found in the area TFR2 belonged to adult female pigs about two years of age. The skulls S1 and S3 were buried close to the altar, while S2 was found in the north-eastern corner of the area TFR2, near the bone deposits SU 014 and 016.

The skull S1 was buried at the south-eastern corner of the altar, probably either in phase 5a or 6.8 The pit in which it was deposited was dug in from a level of 1,96 m ASL and cuts through the SU 003a and 003b and into a previous pottery deposit (SU 112) from phase 5. The skull was surrounded by muddy clay and was bordered by two upright standing pottery fragments, which were placed as a boundary marker for the deposit.

The skull S2 was found in the north-eastern corner of the area TFR2, at the same level as the skull S1, dating it to the early Hadrianic phase 6, as well. The deposit of the skull was not dug through the mortar layer (SU 001c), which defines the transitional period of the sanctuary. Thus, the skull was deposited before the transition of the area from a sacred to a profane area started.

As mentioned above, the deposits SU 016 and 014 were placed in the north-eastern corner of the sanctuary. Both deposits were found immediately underneath the lowest layer of the marble deposit, which covered all of TFR2. The deposits were dug through the previously mentioned mortar layer (SU 001c) and must therefore have been made in the transitional period of the sanctuary (phase 6), possibly one of the very last sacrifices before the sacred area was closed. The deposits were closed-off in a very particular way: SU 016 was dug in right next to the later Hadrianic wall and bordered on its western side by several bricks, which had been stuck into the ground at equal distance. After the animal bones were placed into the pit, cooking ware lids were used to cover it. Some of the lids were found complete and placed leaning.

The bones recovered from the deposits 014 and 016 were better preserved than those found in other contexts. Most of them belonged to larger animals, i.e. an atlas and a shoulder blade from an ox. The shoulder blade had a length of 40 cm. Several near-complete jaws of pigs were also found in these deposits.

The depositions of the three pig skulls, 014 and 016 are the only currently known bone deposits in the sanctuary. Bones were a frequent find, both in deposits that mostly contained pottery and in the layers as well. At the moment, the skulls are being interpreted as a closing ritual of the sanctuary. The use of pig skulls as a closing ritual can be seen in Piano di Comunità in Veii9, where a well was ritually closed off by placing eight pig skulls inside before it was sealed. However, another example of pig skulls being buried in such a way is from the Palatine, at the sanctuary of Magna Mater. Here the skulls were interpreted as being part of the inauguration of the building, as they were found at the foundation of the porticus of Cybele.10

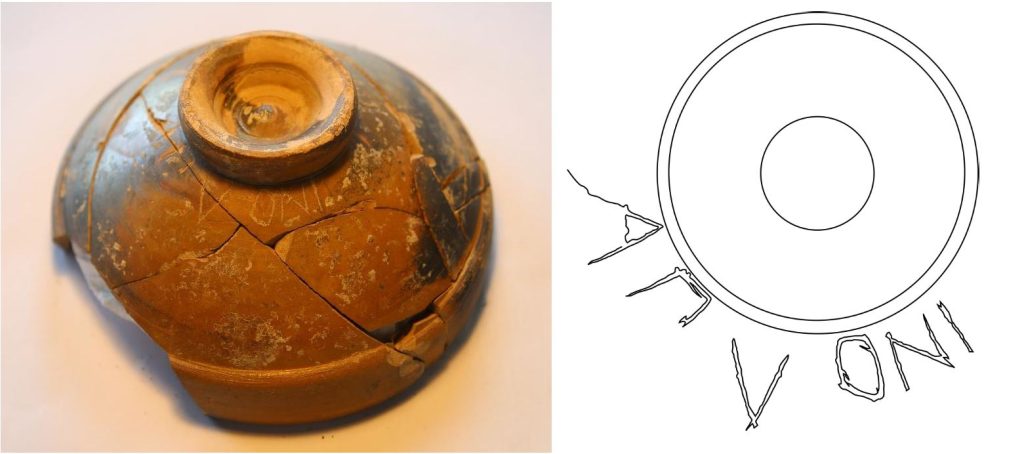

Inscribed Pottery from TFR2

The opportunity to study the ceramic material, which had not previously been available brought on a lot of new exciting finds. Among these finds were several inscriptions in fragments of pottery as well as a complete inscription of a deity’s name.

In total five inscriptions have been found at this point. The four of them are made in black gloss vessels, while one is made in a cooking vessel lid. All the inscriptions have been made with a sharp tool after firing.

The first inscription is an A or X on the interior of the foot of a black gloss bowl. Such inscriptions have been found in other sanctuaries, however, the meaning of it is unclear. It could be a reference to the person who dedicated the vessel but is probably not a reference to the deity. Several A’s have also been found on pottery from other sanctuaries, such as Ardea11 and single letter inscriptions are in general common.12

Next is an A L (or an AU / AT but it is less likely) found on a cooking ware lid. The A is open with the line from the left and down. The type of A is common in the mid. republican period; however, the more common form of the letter has the line starting from the right.13 The inscription is most likely the name of the worshipper.

A fragment of a black gloss bowl has the inscription M I I on the lip. The inscription is possibly incomplete since the vessel is broken right before the M, which could mean that this is the end of the inscription. The M has a shape that dates to the 3rd century BCE.14 The I I should probably be read as an E, this type of E made with two vertical lines starts at the end of the 4th century but also appear consistently in the 3rd century BCE.15

Since the fragment was broken off right before the M but has no further letters after the I I, it is difficult to determine if the ME is the end of the name or is simply just an ME. ME could be the end of a female Greek-inspired name in the dative form. Another possibility is that ME could be a shortening io Menerva (Minerva), however, the inscriber has plenty of room to write the name out, so why shorten it.

A body fragment of a black gloss vessel had the letters I O (or I D) inscribed vertically on the exterior of the vessel. The letters had been made after firing, but unlike the other inscriptions which seem to have been carved with a pointed tool, this inscription was made by making make small “pokes” into the glaze. The fragment is broken right after the O, and it is, therefore, possible that the inscription is unfinished. Reconstructing the angle of the vessel and comparing it to similar bowls show that there would be room for another letter after the O. It is very possible that the fragment was supposed to spell IOVE, IOV, or IOVI, which would be a dedication to Jupiter.

The last inscriptions came from a black gloss bowl found in one of the deposits. The bowl is dated to the first half of the second century BCE (Morel 2534), however, the deposit is dated to the middle to late 1st century BCE. The vessel was placed inside the deposit with a thin-walled cup inside it. The bowl has an inscription on the exterior body, close to the foot of the vessel. The inscription was made with a pointed object post firing. It reads A P L O N I. The name is a Latin version of the Greek Apollon. This version of the name is most probably the dative version of the name, indicating that the offering was dedicated to Apollon.

The area under and around the A is broken, and it is, therefore, difficult to identify the exact shape of the letter. The next two letters are an open P and an L, which both point to a date in the late 4th century.16 The letters ONI, however, date to the 3rd century BCE. This leaves us with a date for the inscription probably at the beginning of the 3rd century.

References

1. Osborne 2004, 2-3.

2. Warden 2009, 107-110.

3. Rieger 2016, 309-310.

4. An article about the altar in more detail is upcoming by Gering, Menge, and Pedersen.

5. For more on the altar of Veii see Colonna 2011.

6. The following numbers and statistics are also part of an upcoming article by Gering, Menge, and Pedersen.

7. Noe-Nygaard.

8. For a better understanding of the levels and phases of the sanctuary, please see miss Menge’s work as my interpretation of the levels is based on that.

9. Ambrosini – Marchesini 2009, 264.

10. Coletti, Celant and Pensabene 2006, 560.

11. See Mento and Ceccarelli 2005.

12. Several examples can be seen again in Ardea, but also in Norba.

13. Ferrante and Nonnis 2018, 216.

14. Ferrante and Nonnis 2018, 216.

15. Ferrante and Nonnis 2018, 216.

16. Ferrante and Nonnis 2018, 216-217.

Literature

- Ambrosini L. and B. B. Marchesini 2009. “Ceramiche a Veio tra V e III sec. a.C.: I dati dello scavo di Piano di Comunità.” in Suburbium II: Il suburbio di Roma dalla fine dell’età monarchica alla nascita del sistema delle ville, V–II secolo a.C. V., edited by V. Jolivet, 1-27. Roma.

- Coletti F., A. Celant and P. Pensabene 2006. “Ricerche Archeologiche e Paleoambientali sul Palatino tra l’età arcaica e la tardoantichità – Primi risultati.” in Atti del convegno di Caserta, edited by C. D’Amico, 557-564. Bologna.

- Colonna 2002. Il santuario di Portonaccio a Veio. Rome.

- Ferrante S. and D. Nonnis. 2018. Ceramica Iscritta dai Dintorni Dell’Acropoli Minore di Norba. in Norba – Scavi E Ricerche, edited by S. Q. Gigli, 205-226. Rome.

- Di Mento M. and Ceccarelli L. 2005. La ceramica a vernice nera. Forme aperte. in: Di Mario 2005, 201–242.

- Noe-Nygaard, N. 1989. “Man-made trace fossils in bones.” Human Evolution 4(6): 461-491.

- Warden, P. G. 2009. “Remains of the Ritual at the Sanctuary of Poggio Colla.” in Votives, places, and rituals in Etruscan religion: studies in honor of Jean MacIntosh, edited by M. Gleba and H. Becker, 107-121. Leiden.

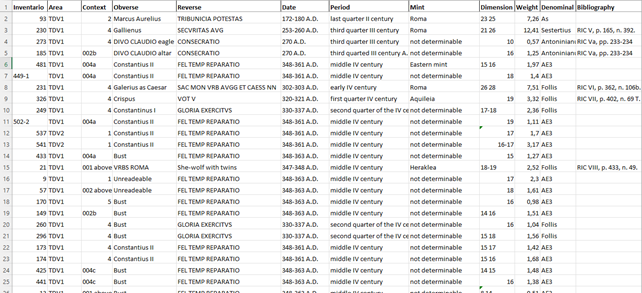

2021-2022 Chapter 3. Coins and Metals in Context

INTRODUCTION

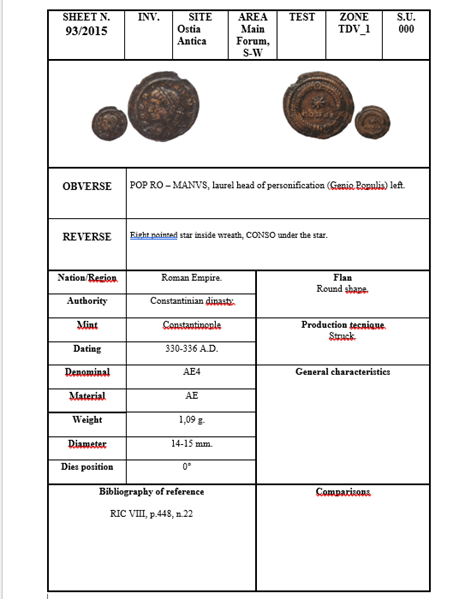

Between the summer of 2021 and the winter of 2022, the cleaning of the entire core of coins from the Taberna Della Venere was continued and completed, with a total of 605 coins. Once cleaned, double-sided photographs were taken, post-production work was done for each of the 1210 photos and the relevant descriptive sheets were filled in. In addition, an Excel spreadsheet was produced to be used as an inventory for the numismatic finds.

At the present stage of the works, it is possible to obtain definitive data regarding the numismatic materials found in the Taberna Della Venere.

Among the 605 coins, 311 AE4, 225 AE3 (including the fractional coins that can certainly be identified in this denominal), 38 specimens that, either because of corrosion or because of an irregular roundel, show characteristics that make it difficult to attribute them to one or the other type, 14 follis (of which only two predate the reductions in weight in the bibliography, while 10 are “light” from the Constantinian dynasty), 3 antoniniani, 2 asses, 1 sestertius, 1 probable provincial bronze, 4 leaden tesserae and 6 coins that, due to their lying in damp soil, have lost any characteristic that makes them recognisable from the shape of the flan (but certainly not AE4 or AE3).

The chronological span covered by these numismatic finds goes from the Trajan era to the reign of Zeno (476-491 A.D.). Although these coins are sporadic, the fact that they both come from sealed contexts makes their discovery very interesting, in terms of hoarding in the first case and as terminus post quem in the second.

Due to the generally low conservation, only 34 coins could be attributed a reference bibliography. In total, 385 coins were illegible (including coins in which only the portrait features of the obverse could be recognised), i.e. 63.4% of the total. Some of the flans appear almost as if they had not been minted, as their surface appears smooth and without any apparent traces of relief, but this characteristic can only be attributed to a long circulation of the coin itself.

METODOLOGY OF CATALOGUING

The manuals used for cataloguing the coins from the Taberna Della Venere comprise almost the entire body of literature on late antique coins. Due to the poor preservation of the material, great use was made of the volume of Guido Bruck[1], in the recent version translated into English. For the distinction of the smaller denominals it was decided to refer to the standard in RIC X[2], and therefore to recognise the AE4 in coins weighing less than 1.50 grams and with a diameter of less than 14 mm, while the AE3 in specimens weighing between 1.50 and 4 grams and with a diameter between 14 and 18 mm. Because of the wide chronological span between the oldest and the newest coinage in the TDV, several volumes of Roman Imperial Coinage have been used, in particular those from V-1 to X[3]. The Late Roman Bronze Coinage[4] has also been used extensively, especially for the part concerning the dating of issues that had a longer course. For monogrammed coins a thematic publication was consulted[5].

THE EXCEL SPREADSHEET

The complete Excel document has been sent to the direction of the Parco Archeologico so that it can be used for future research by academics. The columns relevant to the entire numismatic nucleus found inside the Taberna Della Venere have been set up and filled in, and the following data have been reported:

– Inventory number: for now this is an internal numbering of the excavation of Ostia Forum Projekt, the ideal prospect would be to replace this data with a definitive inventory number found in the archives of the Parco.

– Area: in our case it indicates the Taberna Della Venere, with a division into TDV1, if it is the main room thoroughly investigated, and TDV2, when it is a coin found in the surface layers cleaned inside the second room.

– Context: the layer or context of origin. In the case of layer 001, particular care was taken to highlight which of the two rooms the coin came from, as it is a layer shared by both.

– Obverse: the so-called “obverse” of the coin usually contained the portrait of the Emperor (or a family member or usurper) and the legend with his name and title. It was preferred to indicate the full name, even if it was only possible to read it in part, while in the many cases where it was not possible to read the name but only see the portrait, “Bust” was generically indicated. If not even the features could be read, this was indicated as “Unreadeable”.

– Reverse: the column shows the legends on the reverse side of the coins, even if these are not legible but it is still possible to attribute the coin with certainty to the relevant series of issue. For a much-discussed issue from the late 4th-5th century, such as the one with the figure of the Victoria incedent on the left, the precise legend has been indicated if it is identifiable, otherwise a generic ‘Victoria type’ has been preferred. As for the reverse, if it is not possible to identify anything on the surface of the coin, it has been indicated as ‘Unreadeable’.

– Date: the period in which the particular coin series was minted is indicated, sometimes to the year in special cases (such as for coins indicating the Vota or other precise anniversaries).

– Period: this is an additional indication to the “dates” column, very useful in the drafting of graphs that can include the totality of the material studied, without being too dense.

– Mint: indicates the city where the coin was minted. For some coins where the indication in the exergue was not legible, it was possible to indicate whether the coin was from an eastern mint, using stylistic comparisons for the portrait or epigraphic comparisons on the reverse.

– Dimension: indicates the diameter of the coin. Two numbers are commonly given, the maximum and minimum diameters, as the flan especially in the late antique period, tend to have irregular shapes.

– Weight: the column shows the weights of the individual coins, expressed in grams and with an indication up to tenths of a gram.

– Denominals: with this term in numismatics the type of coin is expressed, it is therefore indicated whether it is an as, a sestertius or other smaller modules, introduced after the reform of Constantius II of 348 AD, the AE3 or AE4.

– Bibliography: only for some coins, for which it was possible to read the legends and the exergue, it was possible to indicate the reference bibliography.

DESCRIPTIVE SHEETS

The data present in the Excel sheet are substantially reported, with the addition of the “Dies position”, that is the positioning (expressed in degrees) of the die of the reverse with respect to that of the reverse. This is particularly important for understanding the type of dies used. Especially in the late antique period, we have clear evidence of the so-called “pincer dies”, in which the coin was positioned to be minted. The fact that they were fixed can be seen from the coins, which usually have an orientation of the minting of the obverse with respect to that of the reverse of 0° or 180°.

The inscriptions present in the legends, in the exergue, in the coin fields has been read and transcribed using the following diacritical marks:

“ / ” = indicates the arrangement of the text on two different lines.

“ – “ = indicates a separation within a normally joined word.

[abc] = integration of reconstructible gaps.

{abc} = deletion of letters considered superfluous.

[. . .] = unreconstructible gap, of which the number of letters is known, each point indicates a missing one.

[- – -] = unreconstructible gap, of which the number of letters is unknown[6].

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Once the lengthy process of cleaning, cataloguing, photographing and arranging the data has been completed, it is planned to write an article in the near future as a preview of what will become the body of the PhD thesis. With the definitive data it will be possible to compose graphs that will allow an immediate and intuitive understanding of the numismatic material found in the various layers of the Taberna Della Venere. The work carried out will also be useful to the archives of the Parco Archeologico di Ostia Antica in order to have an overview of the numismatic material found during the excavations of the Ostia Forum Projekt and to make the material easily available to academics who may request to study it in the future.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Buonopane 2009: Manuale di epigrafia latina, Carocci, Roma, 2009.

Bruck 2014: Late roman bronze coinage, An attribution guide for poorly preserved coins, Geneva, 2014.

Bruun 1966: The Roman imperial coinage. Volume VII, Constantine and Licinius A.D. 313-337, London, Spink & Son, 1966.

Hill – Carson – Kent 1960: Late Roman bronze coinage, A.D. 324-498: part I: The bronze coinage of the House of Constantine, A.D. 324-346 / — part II: Bronze Roman imperial coinage of the later Empire, A.D. 346-498, London, Spink & Son, 1960.

Kent 1981: The Roman imperial coinage. Volume VIII, The family of Constantine I, London, Spink & Son, 1981.

Kent 1994: The Roman imperial coinage. Volume X, The divided Empire and the fall of the western parts AD 395-491, London, Spink & Son, 1994.

Morello 1999: Piccoli bronzi con monogramma (sec.V-VI), Libreria Classica Editrice Diana, Cassino, 1999.

Pearce 1951: The Roman imperial coinage. Vol. IX, Valentinian I- Theodosius I, London, Spink & Son, 1951.

Sutherland 1967: The Roman imperial coinage. Volume VI, Diocletian’s reform (A.D. 294) to the death of Maximinus (A.D. 313), London, Spink & Son, 1967.

Webb 1927: The Roman imperial coinage. Vol. V, part I, London, Spink & Son, 1927.

Webb 1933: The Roman imperial coinage. Vol. V, part II, London, Spink & Son, 1933.

[1] Bruck 2014.

[2] Kent 1994, p. 17.

[3] Webb 1927; Webb 1933; Sutherland 1967; Bruun 1966; Kent 1981; Pearce 1951; Kent 1994.

[4] Hill – Carson – Kent 1960.

[5] Morello 1999.

[6] Buonopane 2009, pp. 136 s.

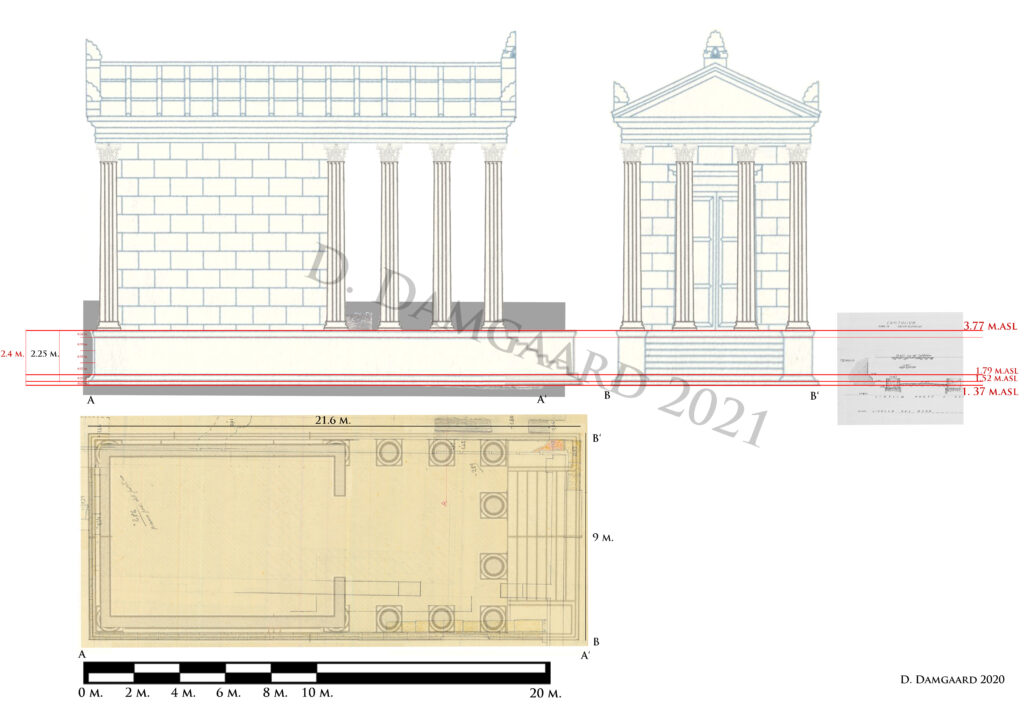

2021-2022 Chapter 6. The first fora of Ostia

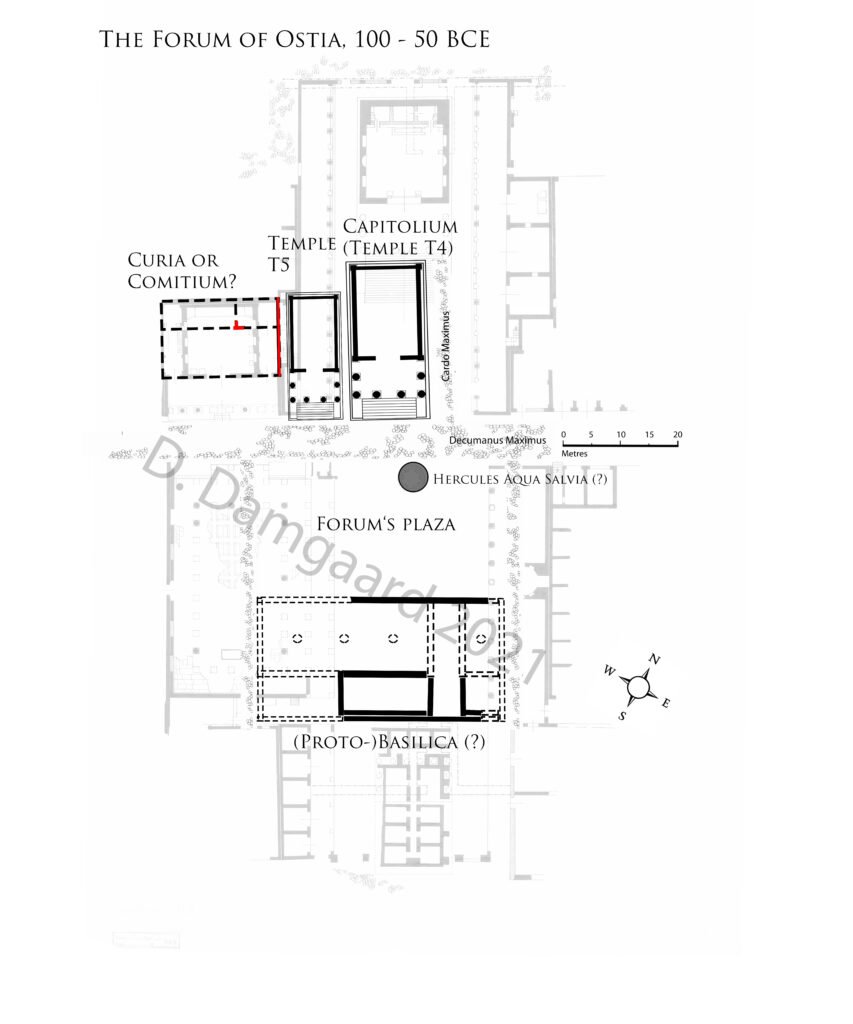

The focus of my work during the last year has been on creating the first theories on the first Forum of Ostia. This has included analysing a vast amount of empirical material from other comparable cities. This has led to the creation of three phases of the Late Republican Forum of Ostia. These three phases are based on archival studies and excavation journals (GdS) in close comparison to comparable cities.[1]

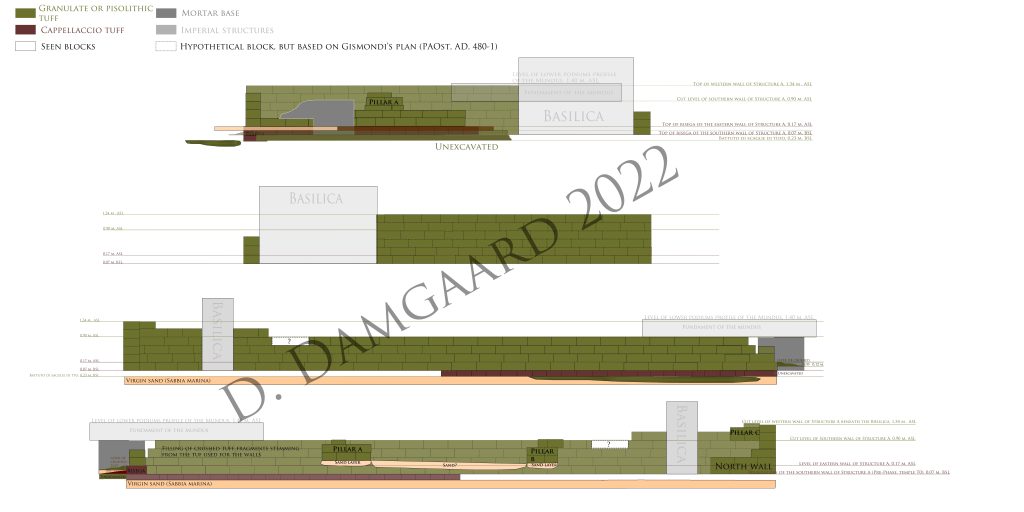

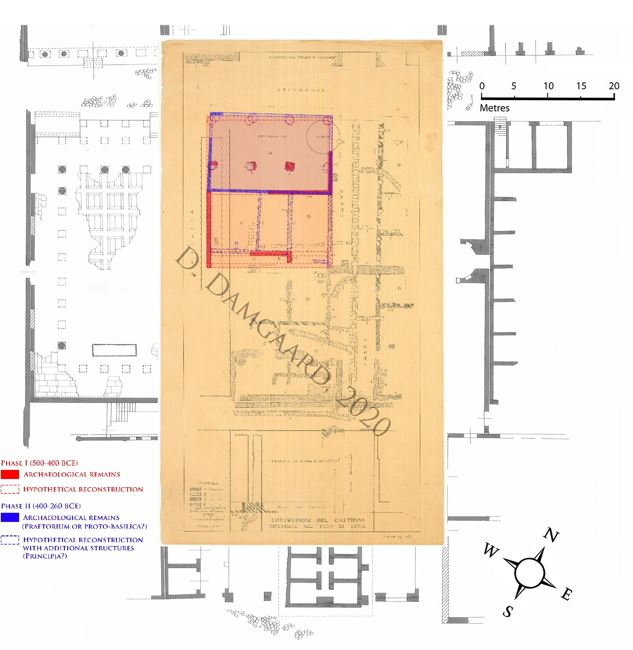

Pre-Phases

In the attempt to create the Forum phases, it was deemed important to scrutinise events preceding the first Forum of Ostia. To be able to do this, a vast amount of work was invested, where all photos and all texts from the excavations conducted in the southern half of the Forum in 1922-1923 were analysed slavishly. Based on photos and text, an attempt to create sections of the trenches was made. By approaching the subject in this matter, a refreshingly new overview emerged of what was actually discovered in the southern half of the Forum during those two years and how the different walls interrelated. One excavation plan has always been used, when discussing the Castrum and (Late) Republican Ostia.[2] Yet, that plan has its flaws, since it provides an insufficient overview of the vast majority of material. Not understanding the interrelation between the walls – especially considering foundation levels of the walls in connection with the utilised tuff – will end with a superficial result. Indeed, there are some references to levels in the published plan, but in comparison to the hand draw plan, it lacks important details.[3] It does provide an overview, but to attempt to differentiate between phases, even the small phases, it is required to study the diaries, old drawings and the photographical archive.

The usage of a specific type of tuff does not necessarily provide an absolute dating of that particular wall. However, it can provide some insight into the relative chronology. Data from several excavation sites does indicate that for example cappellaccio tuff[4] often was used from the 6th through 4th centuries BCE, whereas Grotta Oscura tuff was utilised from the 4th century BCE to the Late Augustan period, thus overlapping the former tuff.[5] The Castrum walls are built in Fidenae tuff, which, according to scholars, was taking into use during the 4th century BCE after conquering Fidenae in 429 BCE.[6] Hence, knowing the material can be of assistance, when attempting to create an interrelation between the walls.

Doing this did provide some insights into the development of the preceding phases and the first phase(s) of the Forum of Ostia (Fig. 1).

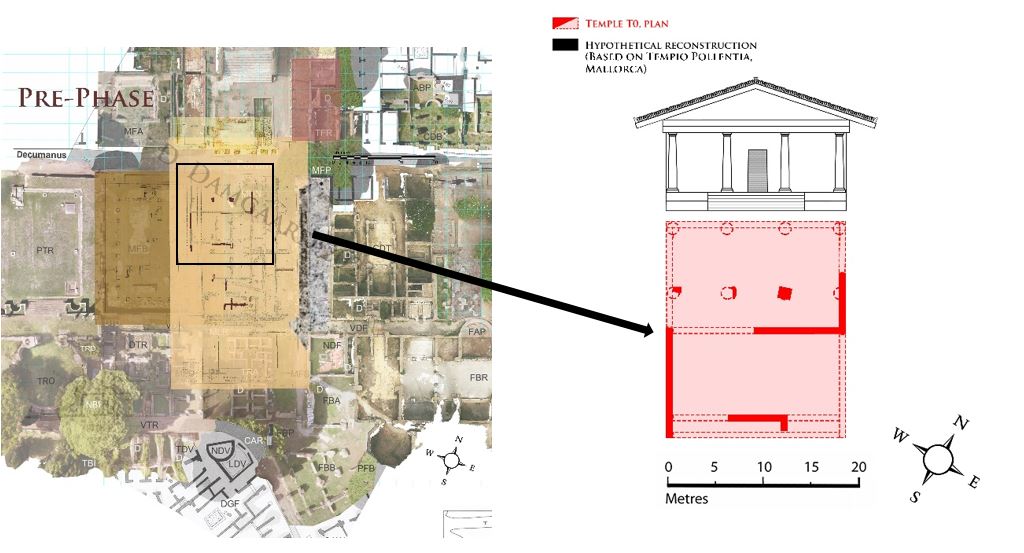

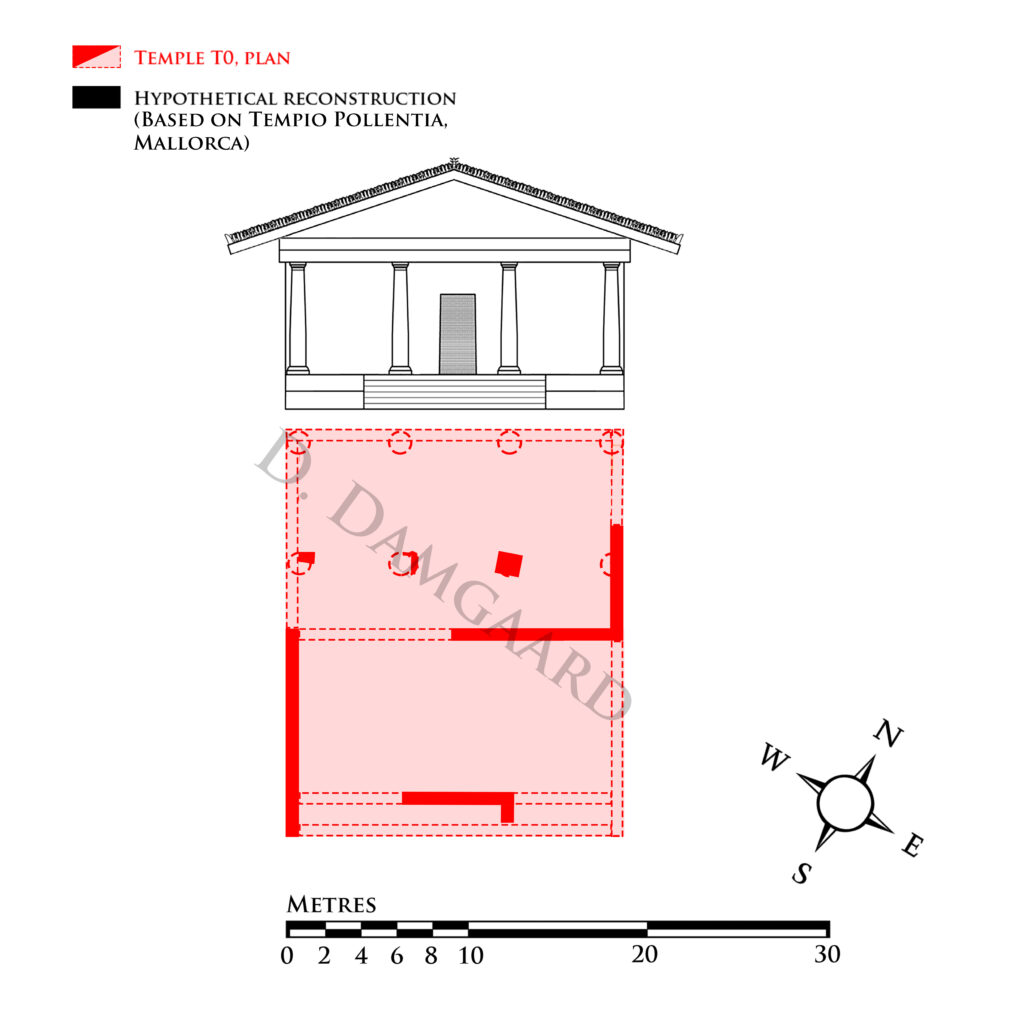

In continuation of this, doing this type of intensive analysis of older plans and photos even further supported a theory about a Late Archaic / late 6th – 5th century BCE structure in the middle of the later Castrum. I have reconstructed this as being that of a temple, since the outline of the lowest row of tuff – the cappellaccio tuff – did underline the contour of a temple-like structure (Fig. 2).[7]

Indeed, reconstructing the temple based solely on fundaments would not be sufficient. There are therefore also inaccuracies, which could speak against the theory, however, the finding of several architectural terracottas in that exact location, does indicate the existence of a temple – or at least of a public building dating to a period preceding the Castrum.[8] The comparisons for the architectural terracottas are nonetheless stemming from contemporary temples around Latium and Etruria.[9]

It does seem as if the temple-like structure was demolished contemporary with the foundation of the Castrum sometime around 300 BCE. The fundaments in cappellaccio tuff of the pronaos were reused after the structure was demolished. A wall of another type of tuff was built on top. This tuff is being described as tufo olivigno. According to Lena, the tuff utilised in the so-called simple constructions in the southern Forum’s plaza all consisted of tufo granulate, which belong to the same type of tuff as Cappellaccio.[10] Nonetheless, in the excavation publications, Guido Calza clearly differentiates between the two types by calling the fundaments Cappellaccio and the tuff above for tufo olivigno.[11] This would therefore indicate that we are dealing with two different types of tuff, but within the same category – in this case that of granulate tuff. In continuation of this, Lena also states that Cappellaccio tuff was very useful for fundaments, wells, cisterns and other moist areas. On the contrary, Cappellaccio tuff does not go well in open air, since it is very fragile when exposed to air.[12] Hence, the blocks above the fundaments must have been better suited for this purpose, and thus of a different kind of tuff – however, still of the granulate type.[13]

After the levelling of the temple-like structure, the pronaos, Structure A, was turned slightly more towards the magnetic north (Fig. 3). Behind Structure A, several buildings were constructed in different kinds of tuff and sandstone – these do also relate to each other in different ways. Sewers and drains were constructed leading out of the different buildings towards the main sewer beneath the Cardo. The hitherto identification of Structure A would be that of a Praetorium or Principium – the main seat for the commander of the Castrum.

Forum Phases

The working hypothesis is that this layout would be the same until the 2nd century BCE. In the period preceding this, Ostia had become the seat of the quaestor Ostiensis (an official taking care of the fleet) in 267 BCE.[14] It is to be believed that in this period, as Ostia gained importance and shortly after the foundation of the Castrum, the first Ostian sanctuaries appeared in and around the Castrum.[15] For instance, the Tempio dell’Ara Rotonda in the Area Sacra Repubblicana has been dated to the 3rd century BCE based on Heraklesschalen.[16] In continuation of this, the newly discovered sanctuary in the centre of Ostia (Sanctuary TFR) cast a new light on the religious landscape in the Castrum in this period. This sanctuary has been dated to before the end of the 3rd century BCE and consists of a temple and an altar with traces of several phases.[17] This sanctuary is placed directly at the intersection between the two main streets, the Cardo Maximus and the Decumanus Maximus.[18] Due to its central position, there are hypotheses that this sanctuary could have been dedicated to Vulcan – the main deity of Ostia. However, in its first phase, it is unlikely that it was dedicated to Vulcan, since it is believed that Vulcan arrived at Ostia during the 2nd century BCE.[19] Several fragments of ceramics that were found during the excavations point toward a sanctuary dedicated to several deities. A bowl with the inscription A P L O N I, which is an Etruscan form of Apollon, was found along with a rim fragment containing the inscription M I I, which can be interpreted as being associated with Minerva.[20]

The temple of this sanctuary was initially facing north, which means that the back wall of the temple would have faced the Decumanus. This would seem a curious orientation, but in the first Castrum phases, the focus must have been towards the Tiber, where Ostia would have her main support line to and from Rome.[21] The existence of the Decumanus as a main street already with the foundation of the Castrum has also been questioned. Indeed, the part of the Decumanus, which is located within the Castrum, is evidenced through the eastern and western Castrum gates, but the Decumanus as a main street to Rome cannot directly be proven. There are some evidence in Ficana, which would support the hypothesis of a street to Ostia already in the Castrum period, and maybe even before, but whether that street would go directly to the eastern gate of the Castrum or to the river harbour is unknown. Furthermore, it is also uncertain whether the street, if it existed in a pre-Castrum period, would follow the same route as the later Decumanus.[22]

Nevertheless, there could be several reasons for the curious orientation of the temple, but one of them could be the Tiber. A northern orientation is also connected to the chthonic deities, which would suit a Vulcan identification though.[23] Additionally, this orientation could also indicate that the sanctuary could date to a period before the foundation of the Castrum. In this period, the Tiber ran closer to the (later) Castrum – the coast of the river would have been situated roughly in the middle between the Hadrianic Capitolium and the end of the northern Cardo.[24] The dating of the Sanctuary TFR does however corroborate the dating of the Castrum as suggested by Martin.[25] At one point, maybe after the creation of the Castrum around 300 BCE, the Tiber shifted its course and moved some 100 metres north and away from the Castrum.[26]

Our research furthermore indicates that in the early 2nd century BCE, some major changes were made to the temple inside the sanctuary. This involved changing the orientation of the temple 180º, which meant that it was now facing the Decumanus. This event probably had an effect on the structures on the opposite side of the Decumanus. Structure B, placed opposite the sanctuary on the southern side of the Decumanus, was levelled at 0.75 m. ASL. Most of the so-called Castrum structures have been levelled at around 1.00 m. ASL. The levelling of Structure B has always been curious, but with the discoveries in TFR, we might be able to explain this. The level of 0.75 m. ASL does also correspond to the levels discovered in connection with the changing orientation of the temple. By levelling Structure B, a plaza was created in front of the sanctuary.

The exact dating of this levelling is uncertain, but based on our research conducted in TFR it is likely that it happened in the 2nd century BCE.[27]

The walls comprising Structure B have always been identified as part of the first Castrum structures, which they also seem to be.[28] Now, with this new aspect, it is therefore possible to write the life history of Structure B. It appears it was constructed together with the Castrum around 300 BCE (maybe built on top of an earlier structure from a period before the Castrum foundation) and was in function until the newly discovered temple opposite the Decumanus changed its orientation from north to south in the 2nd century BCE. The identification of Structure B is unknown, since we only have the western and parts of the southern side preserved. Only one wall, Wall d, divides the structure in two. The length of the northern room is 18 metres and its width is unknown. Regardless hereof, it does seem as if the northern room is quite large, and a well, P1, that was found inside that large room belongs to the first phase of the structure.[29] The shape and size of Structure B lead the thoughts to parts of the palatial complexes of the 6th – 5th centuries BCE, as for instance the Palatial Complex in Pyrgi.[30] However, such an identification of Structure B based solely on three walls and a well is farfetched and near to unlikely in its Castrum phase. Attempting to identify Structure B would require a complete overview of the finds and their contexts, and these are unfortunately not at hand. Nevertheless, the demolishing of Structure B would have had some impact on the local administration, since the Structure B, based on its location and size, would have had a public function. That function was then either removed or relocated during the 2nd century BCE. Its position was replaced by a plaza, and probably the first Forum’s plaza in Ostia. Structures A and C were still standing in this first Forum phase.

I have established the first fora before Augustan times. The first Forum, as shortly introduced above, can be dated to the 2nd century BCE followed by the next phase around 100 BCE and finally the last Forum phase before Augustan times can be dated to the middle of the 1st century BCE contemporary with the construction of the city wall. Events happening in this last phase is evidenced through the inscription mentioning Publius Lucilius Gamala, also known as Gamala Senior.[31]

Regarding the fora, I will also be discussing what actually comprise a Forum. Throughout the decades discussing urbanism and Romanisation, it is clear that no specific definition of a forum exist. There is the ideological definition regarding Roman colonies, of which Ostia is one, put forward by e.g. Paul Zanker, which states that a forum comprise an open plaza, a main temple towards the main street connected to Rome and a basilica and/or a public meeting place such as a comitium or curia.[32] In Cosa for example, a Roman colony founded in 273 BCE, the forum was already planned with the foundation of the town.[33] In addition to this, the main temple of the town, the Capitolium, was not placed in the forum, but on the Arx, which most likely should be seen as an imitation of the situation in Rome, where the Jupiter Optimus Maximus temple was placed on the Capitol Hill overlooking the Forum. The first forum of Cosa thus consisted of an open plaza with the comitium-curia complex in the middle axis of one of the long sides. The three remaining sides consisted of atrium houses, with one of them, Atrium House I, not having any tablinum or triclinium, but tabernae, cubiculae and alae. This was used as an argument for identifying this atrium house as an atrium publicum – a public office containing the state/town archives. It was not until the following forum phase, which has been dated to between 197 and the 1st century BCE that the forum of Cosa got its first temple, Temple B.[34] This therefore indicates that the forum of Cosa initially did not follow the ideological concept of a forum. The question is whether the ideological concept was an original idea or defined later as most fora in the Republic already was built.

Hence, we do not have a clear and exact definition of what a forum comprise. Indeed, we can collect components and institutions needed for a forum with the most obvious component being the open plaza in the centre of a city partly surrounded by buildings, whether those are religious or profane.

“Grid Approach”

Finally, I want to introduce a theoretical approach, I have chosen to utilise. This could be called “Grid Approach”. I have encountered this approach before, but never heard a name for it.[35] It is basically dividing the centre into equally large parcels, and based on these parcels, houses, temples and other buildings can be discerned and on this back drop, the different phase might slowly appear. With the development of the Roman cities, the accumulation of buildings, extensions of the city and the population growth, these lines might be diluted. However, in most cases, it is still possible to discern earlier limits by looking at later structures. More recently, Gering has attempted to reconstruct the centre of Ostia as the Castrum was founded.[36]

Final remarks

Now in the process of my dissertation, I am initiating the intensive analysis of the different buildings. This involves measuring and describing them. I will start the process with the pre-Castrum and Castrum phase, since that makes most sense. In that way, I can create the diachronic perspective, and it becomes possible to maintain an overview of the development of each individual building, which in turn can be used to interpret on the overall development of the centre and Ostia as a city.

I am planning to divide the dissertation into two main parts; Part I is the intensive analysis of the remains. Part II will be the interpretation of it all and its meaning to Ostia as a whole and the possible impact on Rome. These two parts will of course be subdivided into the defined phases.

Before this is going to be possible, I will have to clear several things. There will therefore be an introduction with not only the ‘Problem Statement’, theoretical and methodological approaches and demarcation, but also a chapter concerning the problems with the lack of proper information regarding the excavation history. This also includes the discussion on plans related to the excavations. I have already begun the writing phase, where I introduce the important plans from the excavations in 1922-1924. Two plans are of special importance for the understanding of the entire development of the area including the pre-Castrum phase, the Castrum phase and the first fora phases.[37] It is vital to present these plans and to clarify several aspects. Some of the ideas regarding the pre-Castrum and Castrum phases have already been published.[38]

Bibliography

- Baglione, M. P.; Marchesini, B. Belelli; Carlucci, C.; Michetti, L. M. 2017, “Pyrgi, Harbour and Sanctuary of Caere: Landscape, Urbanistic Panning and Architectural Features”, in Archeologia e Calcolatori vol. 28.2. Pp. 201-210.

- Brandt, Johann Rasmus. 2002, “Ostia and Ficana. Two Tales of One City”, in MeditArch vol. 15. Pp. 23-39.

- Brown, Frank. 1980, Cosa. The Making of a Roman Town. Ann Arbor.

- Brown, Frank; Richardson, Emeline Hill; Richardson, jr, L. 1993, Cosa III. The Buildings of the Forum. Colony, Municipium, and Village. MAAR vol. XXXVII. Pennsylvania.

- Calza, G., G. Becatti, I. Gismondi, G. de Angelis D’Ossat & H. Bloch. 1953, Scavi di Ostia. Vol. I. Topografia Generale. Rome.

- Cuyler, Mary Jane. 2019, “Legend and Archaeology in Ostia: P. Lucilius Gamala and the Quattro Tempietti”, in BABESCH vol. 94. Pp. 127-146.

- Damgaard, Daniel. 2019, “Architectural Terracottas from Etrusco-Italic Temples on the Later Forum of Ostia. Archaic Ostia Revisited”, in Analecta Romana Instituti Danici (ARID), vol. 43 (2018). Pp. 91-109.

- Damgaard, Daniel. 2022, “Traces of Early Ostia: A Late Archaic Temple in the Later Forum of Ostia”, in G. Mainet & M. S. Graziano (eds.), Ad Ostium Tiberis. Proceedings of the Conference Ricerche Archeologiche alla Foce del Tevere (December 2018,18th-20th). Pp. 209-226.

- Gering, Axel. Forthcoming, “The insula as a grid and architectural unit: The role of two recently discovered sanctuaries from an old excavation in Ostia’s centre”, in Sven Straumann (ed.), Insulae in Context. International Colloquium at University of Basel/Augusta Raurica (CH), September 25th-28th 2019.

- Hesberg, Henner von. 1985, “Zur Plangestaltung der Coloniae Maritimae“, in RM, vol. 92. Pp. 127-150.

- Lackner, Eva-Maria. 2008, Republikanische Fora. Heidelberg.

- Lena, Gioacchino. 2011, “Le qaulità di tufo impiegate nell’edilizia ostiense: aspetti geoarcheologici”, in Lavori e studi promossi dal DISMA (2008-2010), (ed. Pani, Clara). Pp. 17-27.

- Manzini, Ilaria. 2014, “I Lucilii Gamalae a Ostia. Storia di una famiglia”, in MEFRA, vol. 126/1. Pp. 55-68.

- Martin, Archer. 1996, “Un saggio sulle mura del castrum di Ostia (reg. I, ins. X, 3)”, in A. G. Zevi & A. Claridge (eds.), Roman Ostia Revisited. Pp. 19-38.

- Menge, Sophie. 2022, Second Interim Report: Theme 2. PhD-Project: The recently discovered Sanctuary on the Forum of Ostia. Ceramics in Context: The Development of the Sacred Area from the Middle Republic to the Hadrianic Period. Online publication (https://ostiagraduiertenkolleg.com/theme-2-interim-reports.html)

- Panei, Liliana. 2010, “The tuffs of the “Servian Wall” in Rome: Materials from the local quarries and from the conquered territories”, in ArcheoSciences, revue d’archéométrie, vol. 34. Pp. 39-43.

- Salomon, Ferréol et al. 2018, “Geoarchaeology of the Roman port-city of Ostia: Fluvio-coastal mobility, urban development and resilience”, in Earth-Science Reviews, vol. 177 (2018). Pp. 265-283.

- Torelli, Mario. 2015, “Conclusioni”, in La scoperta di una struttura templare sul Quirinale presso l’ex Regio Ufficio Geologico (eds. Arizza, Marco & Mirella Serlorenzi). Pp. 185-189.

- Zanker, Paul. 2000. “The city as a symbol: Rome and the creation of an urban image”, in Romanization and the city: creation, transformations, and failures. Proceedings of a conference held at the American Academy in Rome to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the excavations at Cosa, 14-16 May, 1998, JRA Suppl. 38. Pp. 25-41.

- Zevi, Fausto. 1973, “P. Lucilio Gamala senior e i quattro tempietti di Ostia”, in MEFRA vol. 85. 555-581.

- Zevi, F., 2001, “Les débuts d’Ostie”, in Descoeudres J.-P. (ed.), Ostia port et porte de Rome antique. p. 3-9.

- Zevi, Fausto. 2004, “P. Lucilio Gamala senior: un riepilogo tren’anni dopo”, in Ostia, Cicero, Gamala, Feasts & Economy (Papers in the Memory of John D’Arms. Atti della Giornate di Studio del 27 giugno 2002 al Castello di Ostia dedicata al ricordo di J. H. D’Arms) JRS suppl. vol. 57. Pp. 47-67.

- Zevi, Fausto. 2009, “Catone e i cavalieri grassi. Il culto di Vulcano ad Ostia : una proposta di lettura storica”, in MEFRA vol. 121/2. Pp. 503-513.

- Zevi, Fausto. 2012, “Culti ed edifici templari di Ostia repubblicana”, in Ostraka: rivista di antichità vol. speciale. Pp. 537-563.

[1] Unfortunately, I have not been able to consult the GdS regarding the excavations conducted beneath the Imperial Basilica.

[2] E.g. Calza et al. 1953, fig. 21.

[3] The published plan is PAOst, AD B481, which is fig. 21 in Calza et al. 1953. The hand drawn plan is PAOst, AD B480.

[4] Sometimes also referred to as Tufo del Palatino or Tufo Grigio. There is another tuff similar to Cappellaccio, which also comes from Rome and Alban Hills, the Tufo Lionato. See Panei 2010, 40. Furthermore, Cappellaccio tuff can also be referred to as Tufo Granulare (Granulate Tuff) and Tufo Pisolitico (Pisolithic Tuff), see Lena 2011, 17-8.

[5] Lena 2011, 18-20.

[6] Lena 2011, 21.

[7] Damgaard 2019, 100-105; Damgaard 2022.

[8] For the inaccuracies, see Damgaard 2022, 223-226.

[9] Damgaard 2019, 95-99.

[10] Lena 2011, 18-9.

[11] Calze et al. 1953, 72.

[12] Lena 2011, 18.

[13] The Archaic temple at St. Omobono in Rome was built in Cappellaccio tuff – also the walls above the ground level. This temple was built no later than 570 BCE. Pers. comm. Vincenzo Timpano.

[14] Zevi 2001; Salomon et al. 2018, 267.

[15] As mentioned earlier, it is a possibility that there already was a sanctuary in the area before the foundation of the Castrum. However, the hypothesis is that that sanctuary would have been some kind of regional sanctuary, whereas the sanctuaries appearing in and around the Castrum after its foundation are to be considered Roman and Ostian sanctuaries.

[16] Zevi 2012, 556.

[17] Menge 2022, tab. 1.

[18] For more on this sanctuary, I refer to the dissertations of Sophie Menge and Trine Bak Pedersen, and to the ongoing work of Prof. Dr. Axel Gering. See also, Zevi 2009.

[19] Pers. comm. Prof. Dr. Axel Gering. For the arrival of Vulcan in Ostia, see Zevi 2009.

[20] For more on this, see the interim report from Trine Bak Pedersen, Theme 4.

[21] Gering forthcoming.

[22] Brandt 2002.

[23] Torelli 2015, 188.

[24] Salomon et al. 2018, fig. 7.

[25] Martin 1996.

[26] Salomon et al. 2018, fig. 7.

[27] I would here refer to the ongoing work and dissertations of Sophie Menge and Trine Bak Pedersen, and to the ongoing work of Prof. Dr. Axel Gering.

[28] There are indications that the fundament of Structure B is part of an earlier and pre-Castrum phase as well. In continuation of this, in front of the southwestern corner of the structure, a level comprising crushed tuff (It. battuto di scaglie di tufo) – a typical pavement seen in the 7th through 4th centuries BCE – was found at 0.17 m. BSL. This, together with a similar level found directly south of Structure A at 0.23 m. BSL, could be the evidence of the first known pavement and level in the area. Based on the fundament levels of the Castrum walls and southern gate at 0.29 m. ASL, this does indicate an earlier phase, thus a pre-Castrum phase. See PAOst, AD B480 and AD B652.

[29] Calza et al. 1953, 73.

[30] Baglione et al. 2017, 205-208.

[31] CIL, XIV 375. For more on Publius Lucilius Gamala, see Zevi 1973; 2004; Mazini 2014; Cuyler 2019.

[32] Zanker 2000,

[33] Lackner 2008, 80-86.

[34] Brown 1980, 33-35, fig. 38; Brown et al. 1993, 101-103; Lackner 2008, 84-85, 348. The year of 197 BCE is based on the end of the Second Punic War as well as the arrival of 1000 families in Cosa, see Lackner 2008, 84.

[35] Others who have used this approach, also concerning Ostia, is e.g. Hesberg 1985; Brandt 2002.

[36] Gering, forthcoming.

[37] PAOst, AD B480 and B481.

[38] Damgaard 2019; 2022.

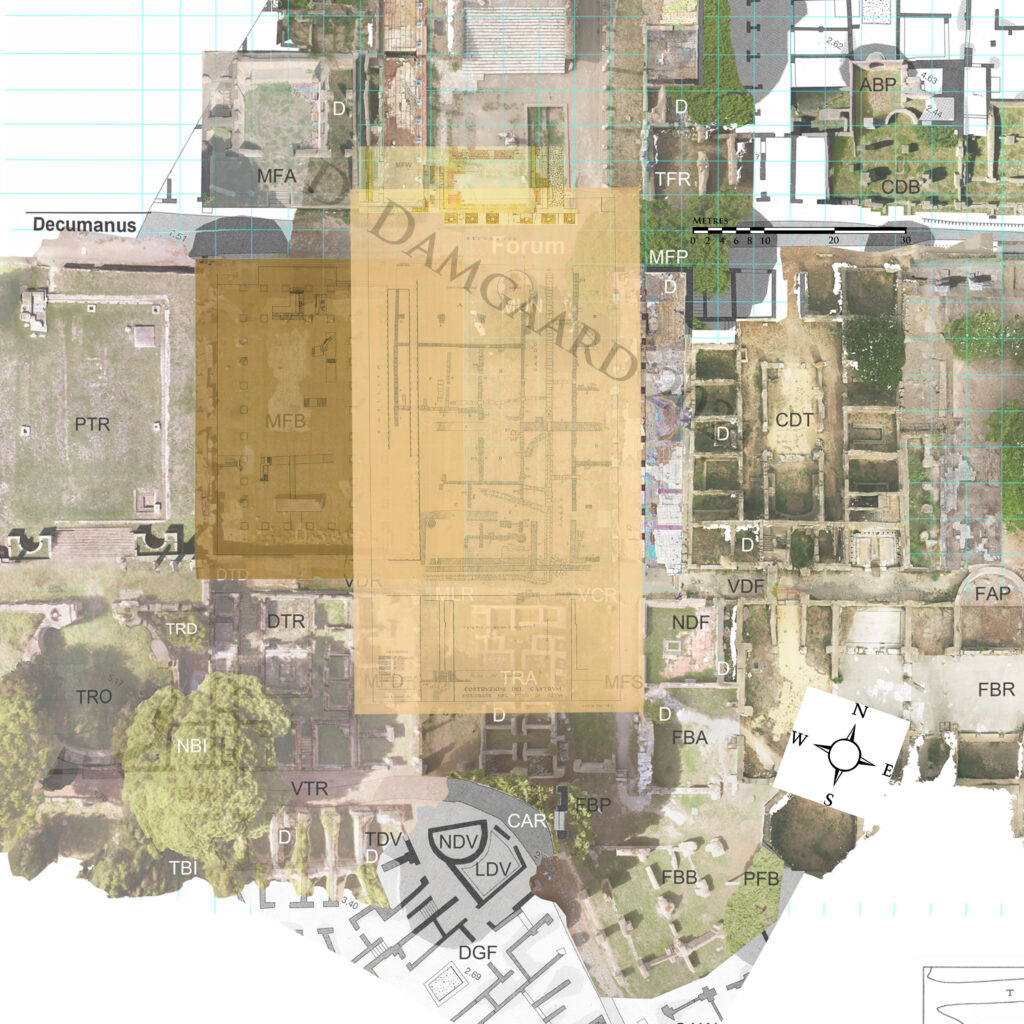

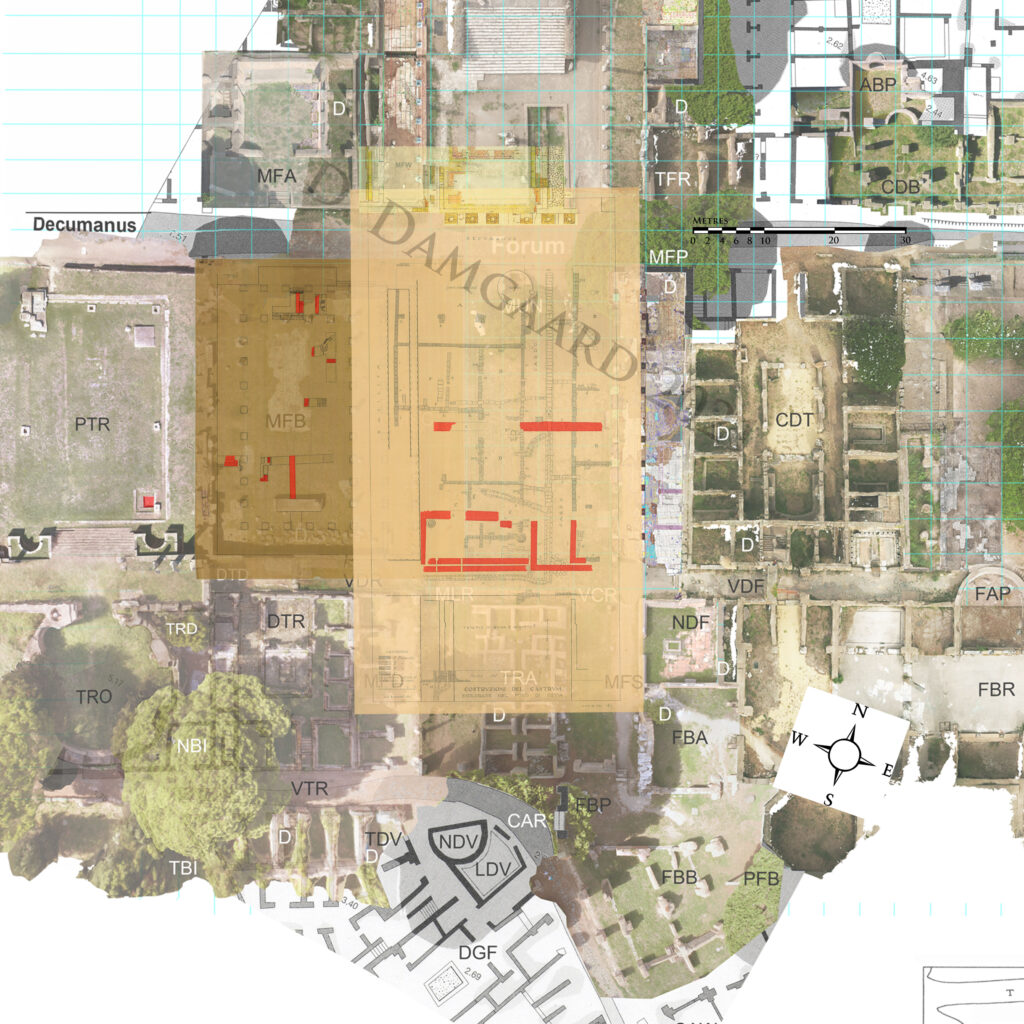

2021-2022 Chapter 5. Building Decor on the Forum of Ostia

2021 has seen a lot of progress with the thesis of Theme 5 of the Ostia Graduirtenkolleg. The working title of this thesis is still ‘Building decor on the Forum of Ostia: For the allocation and reconstruction of the marble furnishing elements of the forum buildings in their original context’ and focuses on documenting and analyzing the vast amounts of architectural marble fragments examined by the Ostia Forum Project (OFP) in deposits/piles around the Forum of Ostia.

The main focus of my work during 2021 has been to document and organize the marble fragments, a large undertaking due to the amount of material. My work therefore has been focused on 1) creating a digital database suited for working with the architectural fragments in question and 2) to gather further data on the fragments using the existing documentation of the OFP from previous campaigns and during a find processing campaign in Ostia Antica in the autumn of 2021.

While the creation of the database and the following compiling of the already available documentation has been very successful, the collection of new data from the material in Ostia was again made difficult by the still ongoing Covid 19 pandemic. Only one campaign was possible during the year due to the pandemic, instead of the usual two – one in the spring and one in the summer. Additionally, a planned stay at the Danish Institute in April, also intended for processing the material, was canceled. I have therefore been forced to rely on the existing photographic documentation, from which I have been able to see what kinds of architectural fragments the deposits contain (fragments from column capitals, bases, architraves etc.). However, this type of documentation the lacks more precise measurements needed for detailed analysis of the fragments, which is best provided by drawings and photogrammetry. Creating a precise typology of the various fragment groups have therefore been difficult. However, on the basis of the existing photographic material, I have been able to expand the database to (at the time of writing) 590 fragments of marble and other fragments. As a result of this, I have been able to find relations between several fragments and then confirming these relations during the field campaign, as will be mentioned below.

The study of old archive material, in the shape of excavation diaries and photos, throughout the 2021 has likewise provided us with further information on the marble fragments with regards to their long-lost find contexts. This becomes especially useful in case where we are able to identify specific marble elements and fragments on photos from the time of excavation, of which two examples will be mentioned below.

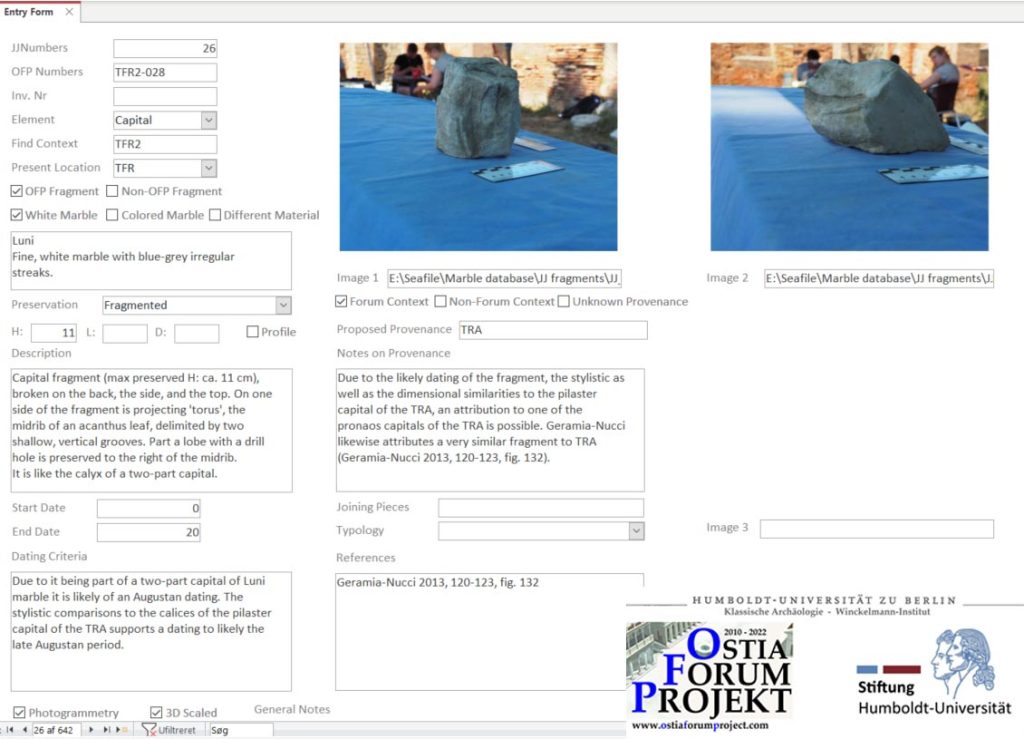

The database

The main objective of this doctoral thesis was and is to create an overview of the hundreds of interesting architectural marble elements found in the deposits around the forum. An essential tool for this endeavor was to create a functional database from which it would be easy to compare and search for specific fragments on several different parameters. The solution was a digital database which is both easy to use and is very customizable in terms of the visual layout. It is possible to create several different searchable fields, which can contain either shorter or longer texts, fields from which it you can select from a few preselected options1, or fields which are simple yes/no boxes. The result was a database, which can make search queries with very specific criteria in mind. This ranges from searching on for example which architectural elements it is (capitals, column shafts, bases, architraves, roof tiles etc.), the type of stone the fragment is carved from (marble, tuff or travertine), the dating of the fragment, or all three combined (Fig. 1).

A further advantage to this database is that allows me to store all the available information on every registered fragment in one place, instead of having it spread out over potentially several other documents, while at the same time having one or several illustrations of the fragment. A specific search results as well as the entire database can likewise be saved as a pdf document or as a printout, allowing for easy transferal of results for various occasions.

As mentioned in the introduction, the database currently contains nearly 600 fragments ranging from small fist-sized fragments to large several hundred-kilogram architectural elements, each identified with its own JJ-number2 (the running number of the database). While the vast majority of the pieces in the database are un-published fragments (OFP fragments) stemming from the forum deposits, some already known and published fragments (non-OFP fragments) have also been added. The reason behind this decision was due to the fact that the database, in its current form, is a working tool for comparing the various architectural fragments of the forum, which includes un-published and published fragments alike. Some examples of already known fragments being in the database are several fragments from the Temple of Roma and Augustus, a lot of which have been extensively published by Patrizio Pensabene and Roberta Geramia Nucci and a cornice section by Pensabene with the inv. no. 29279 (JJ_105 in the database). The latter example will be mentioned below.

Reconstructing lost contexts – clues derived from archive photos

Throughout 2021, the examination of old archive material from the photographic archive and the library of the Archeological Park of Ostia Antica by the OFP has produced some interesting results relating to the lost contexts of some the marble fragments of the forum. The stratigraphic context of archaeological material is a very important element for people wanting to understand the chronological development of an archeological site. The documentation of the stratigraphy and the objects found in it is therefore a crucial part of any present-day excavation. This, however, was not the case in the early 20th century when the forum of Ostia was being excavated. Due to the often-uncomprehensive nature of the documentation of this period, the exact find context of most of the marble fragments found during these excavations were never recorded. As a result of this, valuable information which could have shed light on for example the dating of the fragments and their provenance has been lost. After the excavation, the pieces that were deemed of particular value was moved to secure storerooms in connection to the museum or used in the reconstructions of the forum buildings, while the remaining fragments were collected into the deposits/piles, which can be found around the forum area today. In some cases, it seems that the marbles excavated in the forum area were put on top or reinserted into already existing deposits of marble fragments – some of which were old limekilns or Late Antique stores, or fragments intended for reuse in other buildings3.

An important tool for researching these marble fragments are old excavation photos from the period in which the forum was excavated. This can give us a clue as to the when exactly the deposits were formed and from in areas of the material of the specific deposits were found. This has so far been possible for the deposit, TFR_2, as well as for several individual fragments.

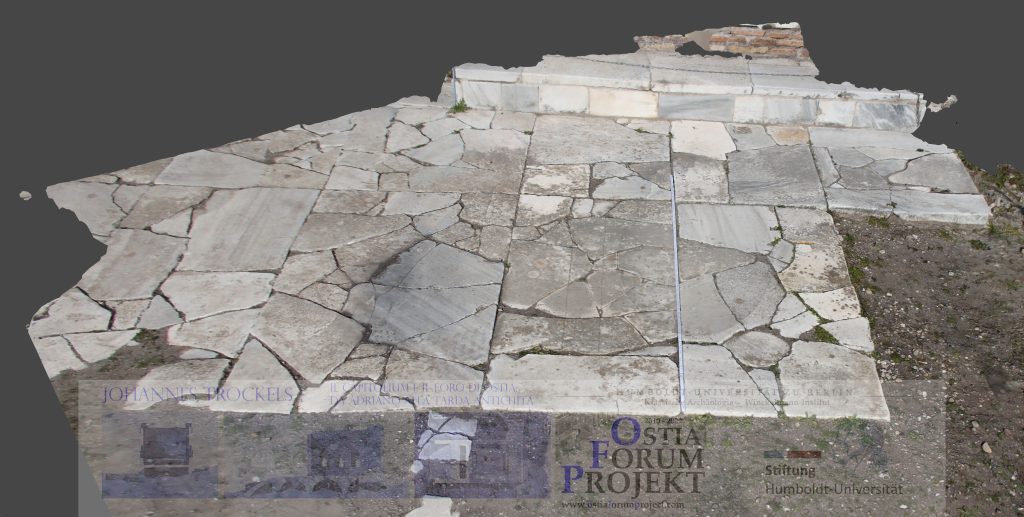

The deposit of TFR_2

The area of TFR (Taberna Forum Rooms) is situated on the eastern side of the forum, just north of the Decumanus. The room of TFR_2 contained the largest of the marble deposits in the forum area (Fig. 2). The deposit contained thousands of fragments, which filled nearly the entire room. This deposit is well known and has been recorded as a yet unlit Antique lime kiln by scholars such as Dante Vaglieri and Raffaele Finelli4 and later by Paolo Lenzi5. However, it was not until 2016, during the examinations conducted by the OFP, that the content of the deposit was thoroughly documented. The deposit, which in some areas reached above a meter in height, can be subdivided into two distinct layers – an upper layer, which consisted of medium- to large-sized fragments and a lower layer consisting of small fist-sized fragments and small marble cut-offs.

The upper layer was characterized by modern vegetation such as pine needles, pine humus and pine-cores in between the stones. This persisted down to the core of the upper layer likely as a consequence of Finelli having mostly excavated the deposit in 1913, after which he put the marbles back into the room. The fact the Finelli put the material back into the TFR_2 seems to be evident in an archive photo from February 1915 where marble is clearly visible in the room.6 In the years after the excavations of 1913, additional material would be deposited in TFR_2 to as late as after 1989 – as indicated by empty chips bags and Coca-Cola cans with a still discernible expiration date found near the surface of the deposit.

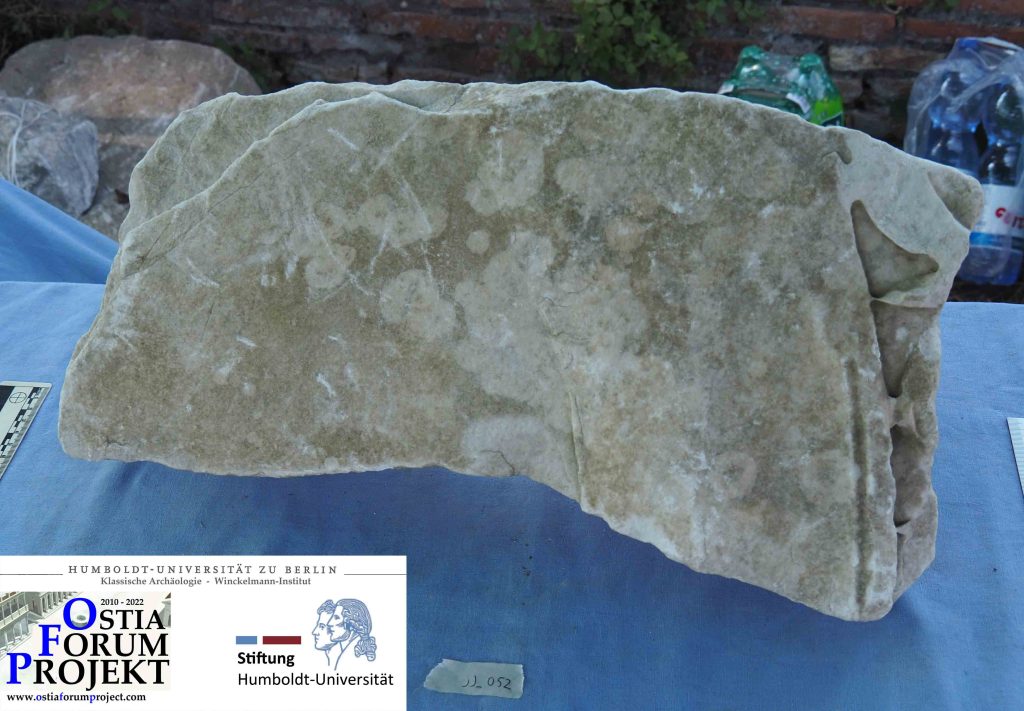

JJ_052

While the presence of a marble deposit in TFR_2 is clearly evident from the archive material, an example of a specific fragment found in TFR_2 can also be found on the old excavation photos. The fragment in question is JJ_052, which was likely part of a clipeus with an anthemion (Fig. 3) can be seen on a photo from March 1913 of the recently uncovered northeastern part of the forum, with the Capitolium in the center7. In front of the Capitolium are two piles of marble fragments, which was found during the excavations roughly in that same area. In the left side of the pile in the foreground of the photo, JJ_052 can be seen, recognizable by its distinct decoration and fragmentation. This revelation shows us two things: 1) that a lot of discarded architectural marble fragments was used as filling material in an ancient level raise of the northern part of the forum and 2) that at some point after the excavations of 1913, at least some the marble material found here was put in into TFR_2 – a reasonable decision due to the proximity of this deposit to the forum. It would therefore also be fair to assume that more of the fragments from TFR_2 would likewise come from the fill layer(s) of the forum, however, this has yet to be thoroughly examined.

JJ_105 (Inv. 29279)

Another object which can be identified on archive photos is the already known raking cornice section decorated with two modillions and two soffits with rosettes, the so-called inv. 292798 (JJ_105 by the OFP). This section can today be seen on the southern wall of the northwest forum porticus and can be found on, not only one, but two separate archive photos.

The earliest photo is from 1924, taken just prior to the start of the excavation of the Caseggiato dei Triclini9. Here, JJ_105 can be seen laying on the Decumanus, immediately opposite the southwestern most of the TFR rooms, TFR_1. Its position here could be an indicator, although admittedly circumstantial, that it was found in the area, possibly also as part of a fill layer of the forum. The second photo of this fragment taking in192510, shows that the cornice had been moved further west along the Decumanus, now placed close to the Mundus, a small circular structure on the forum. The reason for this is unknown, however, it could be due to the excavators needing more space for the excavations in the Caseggiato dei Triclini and therefore opted to move the cornice further away.

Interesting fragments

The research of the past year yielded new insights into the several individual fragments – the majority of which stem from the TFR_2 deposit. Below are two examples of specific interest: a recently reconstructed cornice and an architrave revetment section.

A nearly complete monumental cornice

The fieldwork of 2021 confirmed the relation between three different cornice fragments to be from the same context – namely the fragments called JJ_057, JJ_058 and JJ_059 (Fig 5); something that had not previously been documented. While the relation between the fragments of JJ_058 and JJ_059 was documented in 2020 as being from the same context due to the correlation between the position of the central astragal and dental of both fragments, the relation of JJ_057 was until this point theoretical. JJ_058 and JJ_059, while not joining with each other directly, accounted for the central part of the decoration sequence of the cornice – namely beginning with a blank soffit followed by a ionic kymation (egg-and-dart motif), a bead-and-reel astragal, a dental relief, and a ionic kymation. However, the sima of the cornice i.e., the upper part of the decoration, was missing. Research done in Berlin prior to the fieldwork 2021, showed that the likely candidate for this part was JJ_057, which was decorated with a blank sima, a lesbian kymation, a bead-and-reel astragal, a blank corona and a blank soffit. Seemingly, this fragment would fit with the other two in terms of dimension and the carving style of the astragals. This relation was confirmed upon an in-person comparison of the fragments, which also revealed that JJ_057 and JJ_059 not only came from the same architectural context, but indeed physically fitted together with each other. This discovery means that we in TFR_2 have a nearly complete and previously unknown cornice from a monumental structure likely dated to the Late Augustan or early Tiberian period11. The preserved height of this cornice is 43,5 cm – likely close to the original height.

While the original context of this cornice section is still unknown, the dating of the cornice can provide us with a clue in this regard. An obvious candidate would be the Temple of Roma and Augustus, located on the southern end of the forum and the first building on the forum to be constructed mainly in marble. This temple is dated to the first quarter of the first century CE12 which correlates with the dating of the TFR_2 cornice. The size of the cornice could possibly hint at it being used in the interior of the temple.13 Another candidate of origin for this cornice could be the currently enigmatic ‘crypta et calchidicum’ of Terentia built around the same time, but so far only known from a monumental inscription14, however, that is pure speculation at this point. The origin of this cornice is of great interest, and it is an aspect, I will study further in the coming year.

A revetment plaque with an architrave soffit

Another group of fragments, which is of great interest, is the two fragments of JJ_080 and JJ_072 (Fig. 6) also from TFR_2. These two fragments were, like the above-mentioned cornice fragments, confirmed to be from the same architectural context – namely a section of revetment of an architrave soffit i.e., the lower part of an architrave. These two fragments were, as with JJ_057 and JJ_059, found to have originally been joined together, which gave us the possibility to reconstruct the entire profile of the revetment plaque. This revealed that the architrave would have been roughly 46 cm in width and 12,5 cm in height. It was decorated with a central projecting part running the length of the architrave culminating in both ends by a concave curve. The sides of the architrave are adorned with two fasciae divided by a blank astragal.

The decorative scheme for the soffit, a central projecting area with an outer frame, can be found all over the Roman world – including several examples being found in Ostia. One these is the internal architraves of the Forum’s Basilica showing the same overall shape, but with the central part being semicircular in its profile15. An important difference between these two architraves is that the basilica architraves are carved as part of a massive marble architrave while JJ_080 and JJ_072 is carved as a revetment, meaning that our fragments were used as marble face for an architrave with a brick and concrete core. An example of a brick and concrete architrave can be found in the Villa of Hadrian at Tivoli, where it is used in several porticos16.

The features which show that this fragment functioned as a revetment is mainly seen on carving technique of the upper surface of the fragments – namely that the innermost part of the plaque has been very roughly smoothed with a pointed chisel, while the edges have been smoothed neatly with a tooth-chisel, as seen on the right side of fig. 6. This is due to the fact the outer edges would need to join with the revetment slabs covering the front and back of the architrave and would therefore need to be a smooth as possible to prevent a visible gap between the two elements. The inner part of the architrave soffit, on the other hand, did not need to be as carefully smoothed, since this would be facing the mortar core of the architrave and could therefore not be seen. The rough surface would have the additional benefit of better being able to stick to the mortar than a smooth surface would.

The dating and origin of this architrave is, as of yet, uncertain apart from it being from the Imperial period, where the use of marble was most widespread. This is an aspect that I, as with the cornice, will attempt to find out in the coming year.

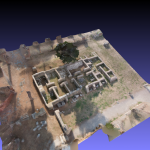

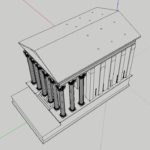

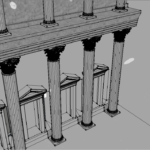

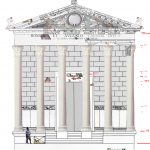

3D reconstructions

An important part of not only my research, but for the OFP as a whole, is the brilliant 3D reconstructions of several buildings from the Forum of Ostia constructed by MA Steven Götz via the software 3D modeling software. These reconstructions are a valuable research tool in several ways, since they allow us to not only visualize how the building would have appeared from several angles at once, but also allows us to test out various different theories as to the building’s appearance and proportions. These reconstructions are capable of integrating photogrammetric 3D models of the actual fragments, which lets us (virtually) insert fragments back into their original position on the building. Alternatively, it is also possible to insert the reconstruction into a photogrammetric model of the forum as it looks today, directly on the remains of the buildings in question. The buildings which have so far been recreated in this manner is the Temple of Roma and Augustus, the predecessor temples of the Capitolium, and the until now unknown sanctuary in the northeastern part of the forum with its different temple phases (T1a-d). While these reconstructions are still a work in progress, they have already revealed a great deal in terms the construction of the buildings and of how the buildings of the forum related to each other.

Future plans for the thesis

The plan for the continued work on the thesis in 2022 will focus on several aspects: 1) finishing the detailed documentation of as many fragments as possible, 2) analyzing the material via the creation of typologies of the various interesting fragments of the marble deposits and 3) the writing the thesis itself. With regards to the remaining documentation of the marble fragments, the planned field campaign of February and March will be crucial. This campaign with be dedicated to thoroughly documenting the most important fragments from the remaining deposits around the forum – mainly the deposits of TRD and DTD located between the Tempio Rotondo and the forum. The priority would be to document the accurate dimensions of the fragments, via either drawings, photogrammetric 3D models or both. The data achieved from these will be essential in dividing the fragments into distinguishable types, which can then possibly be attributed to known buildings around the forum.

A planed stay at the Danish Institute in Rome in May will provide an opportunity for me to find comparisons to my material in Ostia in the city of Rome and its surroundings. Specific areas of interest would be the architectural decorations of the various monuments in Rome such as on the Forum Romanum, the Palatine Hill, the Imperial fora, as well as churches where ancient spolia has been used, such the Basilica di Santa Sabina all’Aventino. I also plan to visit some of the many museums of the city such as the Capitoline Museums, Vatican Museums, and the Crypta Balbi, all of which have a lot of pieces of interest. Outside of Rome itself the site of Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli will be an essential site to visit. A stay in at the Institute will likewise provide me with an opportunity to utilize the city’s many libraries, which will be very useful for writing the thesis itself.

References

- This is very useful for avoiding spelling errors, which would make the criterion in question not show up during a search in the database.

- JJ is an abbreviation of the name of the author of this doctoral thesis, Jesper Jensen.

- For more on the industry of reusing/recutting marbles on the forum in Late Antiquity, see Gering 2016.

- Giornale degli Scavi 1913, 195.

- Lenzi 1998, 259, sito 12.

- PAOst, AF B 2196.

- PAOst, AF, A 2426.

- Pensabene 2007, 264, tav. 77,1.

- PAOst, AF A 2477.

- PAOst, AF A 2462.

- The dating is based the style and depth of the carving of the decoration.

- Geremia Nucci 2013, 162-183.

- For possible reconstructions of the interior of the Temple of Roma and Augustus, see Gering 2020.

- Mar 2002, 118.

- Pensabene 2007, 215, fig. 118, tav. 56, 4-5.

- See for example the Doric portico of the Edificio con Pilastri Dorici.

Bibliography

Giornale degli Scavi, 1913. (Unpublished)

Gering, A. 2016. ’Brüche in der Stadtwahrnehmung. Bauten und Bildausstattung des Forums von Ostia im Wandel.’ in A. Haug – P. Kreuz (editors), Stadterfahrung als Sinneserfahrung in der römischen Kaiserzeit, 2016, pp. 247-266.

Geremia Nucci, R. 2013. Il Tempio di Roma e di Augusto a Ostia. Rome.

Gering, A. 2020. ’Zum Aussagewert umgenutzter Bauteile des Roma- und Augustustempels für die Bau- und Verfallsgeschichte Ostias. Ergebnisse der Spoliensurveys 2016–2018 des Ostia-Forum-Projekts (OFP)’, in K. Piesker and U. Wulf-Rheidt, Umgebaut. Umbau-, Umnutzungs- und Umwertungsprozesse in der antiken Architektur. Internationales Kolloquium in Berlin vom 21.–24. Februar 2018 veranstaltet vom Architekturreferat des DAI, pp. 383-402.

Lenzi, P. 1998. ‚”Sita in loco qui vocatur calcaria” : attività di spoliazione e forni da calce a Ostia.’ In: Archeologia medievale 25, 1998, pp. 247-263.

Mar, R. 2002. ‘Ostia, una ciudad modelada por el comercio. La construcción del Foro.’ In: Mélanges de l’École française de Rome. Antiquité, tome 114, n°1. 2002, pp. 111-180.

Pensabene, P. 2007. Ostiensium marmorum decus et decor. Studi architettonici, decorativi e archaeometrici. Rome.